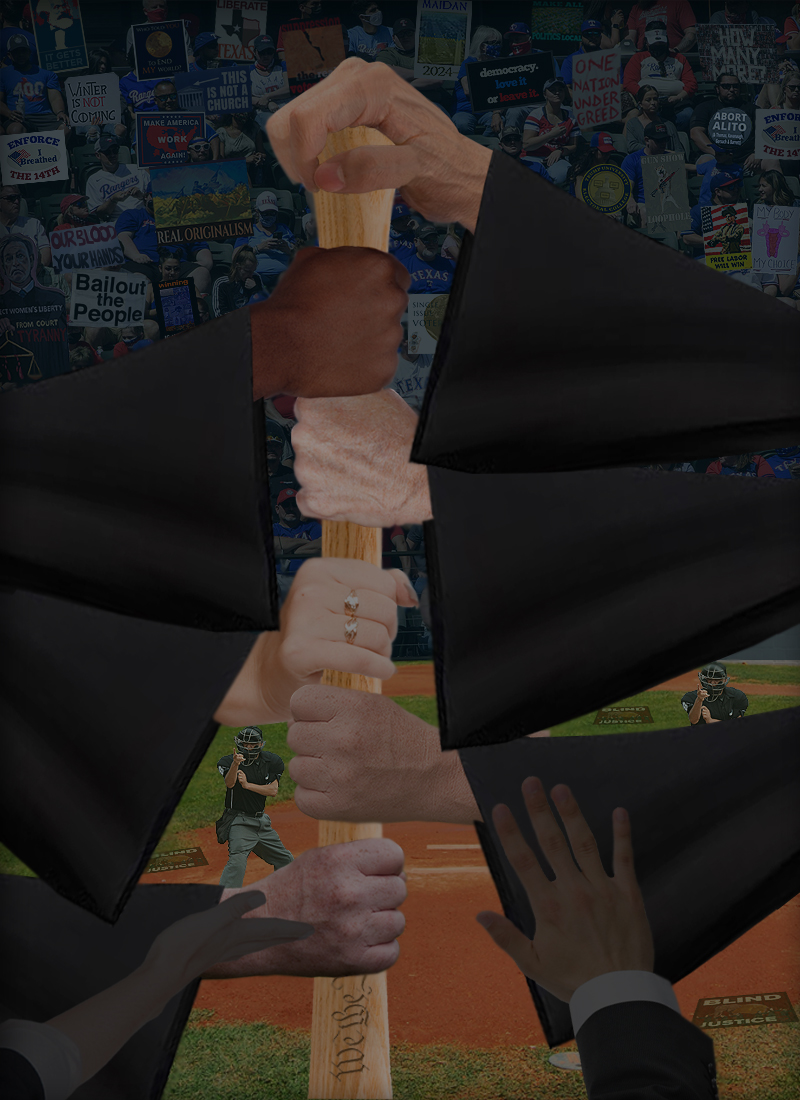

The Supreme Court’s Confirmative, Retrograde, and Disruptive Action

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, July 20, 2023 (Image credits: Tom de Boor, Adobe, Dreamstime, et al)

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, July 20, 2023 (Image credits: Tom de Boor, Adobe, Dreamstime, et al)

There are none so blind as those who will not see.

On June 29, the Supreme Court (SCOTUS), in its decision on two cases (Harvard University and the University of North Carolina), ruled that using race-related affirmative action for admission to colleges and universities violated the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection. The Court’s ruling was a confirmative, retrograde, and disruptive action.

The Confirmative Nature of the Court’s Action

The decision confirmed that the conservative majority (Justices Roberts, Alito, Barrett, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Thomas) on the Court is: (1) as interested in applying their own political and personal philosophies as in interpreting the law and (2) committed to elevating the SCOTUS above the other two branches of the federal government.

The Supreme Court’s ruling this year on the higher education affirmative action cases reaffirms the perspective that we shared regarding the conservative majority in a blog titled “It Should be the Supreme Court — Not a Stomping Ground for ‘Supreme Beings,’” written in July of last year, shortly after the Court handed down two controversial rulings eliminating abortion rights for women and elevating the rights of gun owners across this country.

In that earlier blog, we went into a fair amount of detail on how the mindsets of the conservative judges influenced their decision-making, so we will not do so here. What is important to address is the direction in which the majority has been and is taking the Court and the impact it will have on the future of governance in the United States.

To do this, we draw upon the insights of two legal experts: Josh Chafetz and Steven Vladeck.

Chafetz is a law professor at Georgetown University and author of Congress’s Constitution. Early in an article in the New York Times published on June 2, about one month before the Court’s affirmative action decision, he states,

“Over roughly the past 15 years, the justices have seized for themselves more and more of the national governing agenda, overriding other decision makers with startling frequency. And they have done so in language that drips with contempt for other governing institutions and in a way that elevates the judicial role above all others.”

Chafetz proceeds to examine decisions on campaign finance law, congressional oversight, and federal regulation, concluding:

“In all of these areas and in plenty more, the justices have seized for themselves an active role in governance. But perhaps even more consequentially, in doing so, they have repeatedly described other political institutions in overwhelmingly derogatory terms while either describing the judiciary in flattering terms or not describing it at all — denying its status as an institution and positioning it as simply a conduit of disembodied law.”

Vladeck is a law professor at the University of Texas and the author of The Shadow Docket: How the Supreme Court Uses Stealth Rulings to Amass Power and Undermine the Republic. (“Stealth Rulings” are emergency rulings or orders that are issued without public hearings or explanations.)

In his book, Vladeck points out that these rulings had been used infrequently, but they expanded considerably after 2017, being employed in areas such as restrictive voting laws, abortion bans, and COVID-19 vaccine mandates.

On July 4 after this year’s court term was completed, Ruth Marcus, associate editor and columnist for the Washington Post, published an interview with Vladeck regarding the Supreme Court’s most recent term (2022 -2023).

In the interview, Vladeck opined that this Supreme Court term was:

Reaffirming, as in reaffirming that last term (2021–2022) was not an aberration. The thread that ties together almost all of the cases of the term is just how much power they all contemplate the courts exercise…For anyone who thinks that judicial restraint is an important principle, this term shows very little of it.

During the interview, when asked by Marcus about the use of the shadow docket this term, Vladeck responded:

…With the summer still ahead of us, there have been five grants of emergency relief [this term]. Three of those were uncontroversial or at least not closely divided. The other two were clearing the way for an Alabama execution and the Title 42 [immigration] order. That’s still more than we would have seen 10 years ago but it’s a lot less than we’ve seen at any point since the beginning of the Trump administration…

To sum it up, by exercising and expanding its unregulated decision-making authority in the light and in the shadows, the Supreme Court is emerging as by far the most powerful branch of the federal government.

As we have written in earlier blogs, the Supreme Court has become too powerful. It is accountable to no one. Moreover, given the breakdown of the governance system within the executive and legislative branches in the United States over the past decade or so, and the virtual standstill on many issues, power is ceded to the Court.

The Supreme Court is not a representative body. It is not a democratic body. But it is the body that may have the ultimate and final word on many of the most critical issues of our times.

The Retrograde Nature of the Court’s Action

And what the Court has done with its affirmative action ruling — just as it did on the abortion rights ruling — is to use its unrivaled authority to move our democracy backward rather than forward. It has moved this nation backward in time to a period when equal rights for all was a promise in writing, but there had been no significant progress in delivering on that promise.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor calls out this reverse engineering in her strong dissent to the affirmative action decision. In that dissent, she writes, “Today, the Court stands in the way and rolls back decades of precedent and momentous progress.”

In his opinion, written for the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts attempted to justify the affirmative action decision by writing, “The student must be treated on his or her experiences as an individual — not on the basis of race.” Clarence Thomas, in his concurring opinion, stressed that the Constitution “is color blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.”

This debate on the need for and appropriateness of affirmative action carried on into the justices’ statements after the decision was announced in the Court. Justice Clarence Thomas and Justice Sonia Sotomayor both benefited from affirmative action policies to get into elite law schools.

In her Washington Post article, Ann E. Marimow notes that in his prepared remarks, which he read, Thomas stated, “Treating anyone differently based on skin color is oppression.” As a counterpoint, Sotomayor stated, “Ignoring racial inequality will not make it disappear.”

Marimow also observes that

“Thomas has written that after graduating from Yale Law School, he “felt racial preference had “robbed my achievement of its true value,” In contrast, Sotomayor has called herself the “perfect affirmative action child’ and the practice opened doors for her at Princeton and Yale, where she excelled alongside her more privileged peers.”

These starkly different positions are revealing. They show that blindness to the reality or refusal to acknowledge the socio-economic fabric and racist history of this country can lead to arguing for “colorblindness”.

That argument is based on personal beliefs rather than facts.

In this regard, reflect on Chief Justice Roberts declaring that “the student must be based upon his or her experiences as an individual — not on the basis of race.” And Justice Thomas declaring: “Treating anyone differently based on skin color is oppression.”

First, look back to the 50’s and 60’s in the United States, when students of certain races experienced being excluded from classrooms, persecuted for being in certain schools as a distinct minority and, in the larger sphere, not being allowed into restaurants, hotels, restrooms, not having the right to vote, and even being lynched and killed because of their race.

Now look around today, and see those students who grew up in poor neighborhoods with inferior schools who have done their homework, excelled, and demonstrated that when given the right access, opportunities, and support in college they can compete with anyone and serve as exemplars of the American dream.

The Supreme Court’s affirmative action decision is revisionist because it ignores nearly 250 years of this nation’s existence based upon “originalism.” The National Constitution Center defines originalism as “a theory of the interpretation of legal texts, including the text of the Constitution.” The Center goes on to explain, “Originalists believe that the constitutional text ought to be given the original public meaning that it would have had at the time that it became law.”

According to an article written by Ilan Wurman, associate professor at law at Arizona State University, published in The Conversation in July of 2022 after the abortion rights and gun rights decision, “Four of the current conservative justices, Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett are proclaimed originalists. Samuel Alito is a “pragmatic originalist.” And Chief Justice John Roberts tends toward pragmatism.

Michel Waldman presents a convincing case against originalism in an article for the Brennan Center for Justice that he wrote in June of 2022. In his article, he notes:

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. rebuked the first arguments for originalism in the 1980s. “We current Justices read the Constitution in the only way that we can: as twentieth-century Americans,” he said then. “We look to the history of the time of framing and to the intervening history of interpretation. But the ultimate question must be: What do the words of the text mean in our time? For the genius of the Constitution rests not in any static meaning it might have had in a world that is dead and gone, but in the adaptability of its great principles to cope with current problems and current needs.’

Waldman concludes his piece by stating:

Brennan’s basic point was enduring and right: the only way a great nation can govern itself is to recognize that the Constitution respects and advances the great goals of freedom, dignity, and democracy in a changing country in changing times. Right now, as used by this Court, originalism just provides cover for a right-wing political agenda.

We conclude this section by remembering that our Constitution is and never has been a static document. The Constitution as approved by the delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 was the product of a compromise and changes. It was not ratified by the states until 1790, after close votes in several state legislatures.

It took from 1790 to the conclusion of a civil war for former slaves to be given the ostensible right to vote by the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. Actually, African Americans didn’t get unimpeded voting rights until after the Twenty-Fourth Amendment, eliminating the payment of a poll tax, was ratified in 1964. Moving from race to sex, women did not get the right to vote until the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920.

As George Santayana famously said, “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Modifying Santayana’s admonition, we say, “Those who want to return to and live in the past are limiting the future of others.”

The Disruptive Nature of the Court’s Action

We start this section of our blog by confessing that we had originally titled it “The Destructive Nature of the Court’s Action.”

Then we realized that the final consequences of the Court’s affirmative action ruling would be determined not in the short term, but over the long term, in response to the decision. That response can and will be shaped by citizens who have the patience, passion, and persistence to persevere in taking corrective actions to address the court’s disruptive action.

There is no question, however, that the Court’s actions will be disruptive and reduce progress and opportunities in the near term. The evidence to support that conclusion comes from a variety of sources. The most persuasive we have seen comes from a June 29 Washington Post column by Ruth Marcus on the progress that had been made which is attributable to affirmative action.

In her column, Marcus draws upon findings from Allison D. Burroughs, a U.S. District Judge, in response to data advanced by Richard Kahlenberg, the expert who consulted to the Students for Fair Admissions (SSFA), the group that brought the Harvard affirmative action case. Burroughs found that “Kahlenberg ‘convincingly establish [ed] that no workable race neutral alternative will currently permit Harvard to achieve the level of racial diversity it has credibly found necessary for its educational mission.”

In fact, “Kahlenberg’s simulations of race-neutral alternative admissions policies ‘uniformly suggest’ that African-American representation in Harvard’s incoming class would fall nearly one-third to approximately ten percent.”

Marcus adds data from California ,which stopped taking race into account in admissions after the passage of Proposition 209 in 1996. After that proposition passed, she states, “Diversity dropped precipitously, particularly at the most selective campuses. Before Proposition 209, 6.32 percent of Berkeley freshmen were Black. In 2019, that number dropped to 2.76 percent…”

Marcus highlights the statistical impact of affirmative action. Two Washington Post local columnists, Courtland Milloy, an African American, and Theresa Vargas, a Mexican-American, told the personal impact in their columns in the Post.

Vargas opens her column by writing , “If it weren’t for affirmative action, I wouldn’t be writing this column.” She proceeds to describe her journey from “a crowded high school on the Southside of San Antonio” to gaining admission to Stanford University. She goes on to explain, “I am telling you this for the same reason that many Black and Brown people have been sharing how affirmative action benefited them — so you see us, so you understand why the Supreme Court’s ruling that colleges cannot consider race in admissions feels so personal.”

Milloy, in his column, discusses his difficult journey from growing up in racially segregated Shreveport, Louisiana in the 60’s, to going to college at Southern Illinois University, to working at the Miami Herald and then moving to the Washington Post. He notes that the impact of affirmative action on him has been “profound.”

Milloy closes his piece by stating, “In my career, affirmative action brought me a long way. But some of the worst parts of 1950’s Louisiana have caught up. And the principles that Thomas (Supreme Court Justice Clarence) says are “so clearly enunciated in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States don’t seem to be much help.”

Milloy nails it. Saying it is so does not make it so. Making it so requires affirmative action.

Corrective Actions for the Supreme Court’s Action

Given that the Supreme Court has ruled against affirmative action, what can be done to correct its confirmative, retrograde, and disruptive action?

There is no single or simple answer to that question. There are a number of potential corrective actions, however, that could be taken. We discuss them later in this section.

It is unlikely, however, in the near term that a broad national reinvention of affirmative action will be forthcoming. One reason for this is that, unlike the Court’s abortion rights decision, which evoked outrage across the country, there has only been a lukewarm response to the Court’s affirmative action ruling.

William Galston, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, provides the following data from various sources in a Brookings Commentary on the public response to the Court’s decision:

- Registered voters backed the Court’s decision 60% to 29%

- White Americans favored the decision by a margin of 42 points, 65% to 23%.

- Surprisingly, only 1 in 5 Black respondents thought that they had personally benefited from affirmative action in college admissions or hiring decisions.

Another reason that a systemic reversal is unlikely is the current composition of the Supreme Court, and the Court’s evolution over the nearly two decades of Chief Justice John Robert’s tenure.

Today’s conservative majority is a “super majority” comprised of six out of the nine justices. Three of those justices: Barret, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh, are Trump appointees and absolute originalists. Given their “relative” youth, and the fact that there are no term or age limits for Supreme Court justices, these three will likely be on the bench for decades to come. During those decades, they will probably never support higher education affirmative action of any type.

Add to this the fact that the Court itself is much different than it was eighteen years ago in 2005, when John Roberts became Chief Justice. Linda Greenhouse, a Pulitzer Prize winner and a reporter on the Supreme Court for the New York Times from 1978 to 2008, examines that difference in her July 9 Guest Essay for the Times.

Near the opening of her essay, Greenhouse observes that there has been a “transformation” of the “constitutional world” during those eighteen years. She advises:

To appreciate that transformation’s full dimension, consider the robust conservative wish list that greeted the new chief justice 18 years ago: Overturn Roe v. Wade. Reinterpret the Second Amendment to make private gun ownership a constitutional right. Eliminate race-based affirmative action in university admissions. Elevate the place of religion across the legal landscape. Curb the regulatory power of federal agencies.

After that, Greenhouse describes how each item on the “conservative wish list” was transformed from a wish to a reality. She closes her essay by asserting:

My focus here on what these past 18 years have achieved has been on the court itself. But of course, the Supreme Court doesn’t stand alone. Powerful social and political movements swirl around it, carefully cultivating cases and serving them up to justices who themselves were propelled to their positions of great power by those movements. The Supreme Court now is this country’s ultimate political prize. That may not be apparent on a day-to-day or even a term-by-term basis. But from the perspective of 18 years, that conclusion is as unavoidable as it is frightening.

We agree with Greenhouse’s assessment. In this 21st century, we are living at a time when the justices on the Supreme Court not only issue rulings — they are assuming the role of rulers.

They are not being given crowns to wear, but they don’t need them. That’s because they operate in an insulated manner, and in isolation from the constraints that affect the majority of those who work in the political and governance spheres. To date, the justices have resisted any recommendations to rein in or modify their mode of operations.

Nevertheless, there are corrective actions that could be taken specifically in response to the affirmative action decision, and more broadly to reduce the justices’ unbridled influence.

In terms of affirmative action, the New York Times and the Congressional Research Service have advanced some thoughtful proposals.

On July 5, the Times published ideas from a number of experts on what could be done to fix college admissions now. They included: creating feeder schools to prep students for entry to college; developing targeted courses and curriculum for those planning to apply for college; improving the community college connections to colleges; focusing on class instead of race in directing more money and support to historic Black colleges and universities; involving college students in outreach recruitment and mentoring of students; asking the elite institutions (e.g., Harvard, Yale and Stanford) to support initiatives to make college admissions more inclusive and equitable.

On June 30, the Congressional Research Service issued a CRS Legal Sidebar titled “The Supreme Court Strikes Down Affirmative Action at Harvard and the University of North Carolina.” That sidebar, prepared for the members and committees of Congress by April J. Anderson, Legislative Attorney, “considers the Court’s history racial classifications in higher education admissions, examines the majority opinion in the two cases, and addresses considerations for Congress.”

The considerations section of the Sidebar reads as follows;

Congress cannot change the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause. Congress could, however, amend Title VI so that it is no longer interpreted congruently with that provision.

Congress could expressly encourage or require diversity-enhancing measures under Title VI. Congress could not require unconstitutional action, such as mandating racial quotas or the kinds of admissions programs struck down by the Court in Students for Fair Admissions. It could require or encourage schools to take other measures, such as tracking minority recruiting, admission, and retention; developing plans to enhance minority recruiting or retention; or appointment of diversity coordinators, Title VI coordinators, or advisory committees. Congress could also consider encouraging or requiring colleges to employ non-racial admissions criteria that may enhance diversity, although it is not clear how the Court might rule on such measures.

It is unlikely that a divided Congress, with a slim Republican majority and the Freedom Caucus in the House, would amend Title VI of the Equal Protection Clause, but the range of options presented are thought-provoking.

This brings us to two broader courses of corrective action that could reduce the stranglehold the Supreme Court has on the country’s current governance system. They are constitutional amendments and reform of the Supreme Court itself.

In a July 1 New York Times Guest Essay, Jill LePore, professor of history at Harvard and director of the Amendments Project, articulated the need and provided recommendations for amendments to our U.S. Constitution.

In her piece, LePore points out that, “The U.S. Constitution hasn’t been meaningfully amended since 1971. Congress sent the Equal Rights Amendment to the states for ratification in 1972, but its derailment rendered the Constitution effectively unamendable. It’s not that people stopped trying. Conservatives, especially, tried.”

She explains why amending the Constitution has been so difficult and states:

Troublingly, our current era of unamendability is also the era of originalism, which also began in 1971. Originalists, who now dominate the Supreme Court, insist that rights and other ideas not discoverable in the debates over the Constitution at its framing do not exist. Perversely, they rely on a wildly impoverished historical record, one that fails even to comprehend the nature of amendment.

From there, LePore moves on to describe the amendment process and how her Amendment Project has accumulated an archive of failed amendments that have been proposed throughout the years. She concludes her piece stating:

Supreme Court term limits, presidential pardon power, congressional apportionment, parental rights, abortion rights, fetal rights, the debt ceiling. It’s all in there.

No one has ever taken stock of this history of failed amendments, an America that never was but was wanted by some, and sometimes by very many, or even most. Americans won’t be able to agree anytime soon on how to amend the U.S. Constitution and will instead face the ongoing risk of “commotions, mobs, bloodshed and Civil War.”

Amending is what makes the Constitution everyone’s. But until the Constitution can once again be amended, only the court can change it. And if that bench insists, perversely, illogically, and in defiance of the very idea of constitutionalism that all change must be rooted in the past, its justices have got a whole lot of reading to do, into a richer, wider, better history.

LePore provides food for thought and a treasure trove for action by those good citizens who want to get engaged in doing the work and making the changes required to ensure that our nation belongs to we, the people, and not to a select few who wear the robes in the Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C.

In our opinion, one of those essential changes that is required is to reform the Supreme Court itself. We first discussed the need for that reform in our book, Working the Pivot Points; To Make America Work Again, published in 2013.

Most recently, in our blog, posted on July 7, 2022, we wrote:

The good news is that quality work has been done to examine the pros and cons of Supreme Court reform.

In April 2021 President Joe Biden issued an executive order establishing the Presidential Commission of the United States, a bipartisan group of experts to examine the issues related to reform of the Court. The Commission submitted its analysis in a final report, which included arguments for and against changes, but no definitive recommendations, in December 2021.

The major changes that were analyzed included: expanding the Court beyond nine justices; establishing term limits; and creating a “code of conduct.” On May 16, Democracy Docket commented that the Commission did support one direct recommendation: “to create an advisory code of conduct.”

That was the situation in July of 2022. Now, in July of 2023, as Tyler Page notes in his July 4 Washington Post article, after the Court’s affirmative action and other “partisan decisions” and the disclosures about Justice Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito getting free air travel and “lavish trips” from rich supporters, there is increasing pressure from Democratic groups and others to move beyond studies and to do something to “revamp” the Court.

The need to do something rather than nothing has become more apparent and crucial. That said, we leave you with these thoughts from the ending of our 2019 blog on the Supreme Court.

We believe in a strong, independent and impartial judiciary. We need that for the sake of, and to preserve, American democracy.

This is why we need new rules of engagement for the Supreme Court. We need to reform the Supreme Court in a manner that ensures that it has the balance and provides the balance of powers envisioned by the founders.

If it becomes merely an extension of a political party or an ideology, it puts the future of this democracy at risk. A democracy at risk cannot long survive.