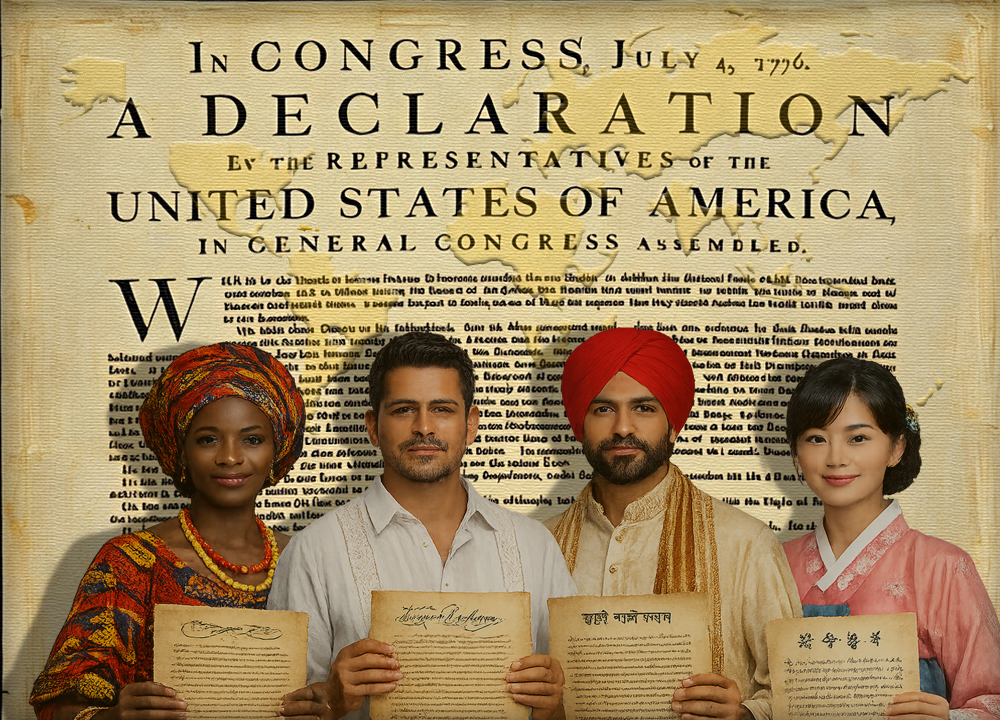

The Declaration of Independence: Evolution. Devolution?

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, February 10, 2026 (Image credits: Tom de Boor, JNCGPT52)

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, February 10, 2026 (Image credits: Tom de Boor, JNCGPT52)

PART II

[This is the second part of a two-part blog on The Declaration of Independence. In Part 1, we addressed the role the Declaration played in the American Revolution. In this part, we examine the connection between the Declaration and the evolution of our democratic form of government, here in the United States, and its contribution to the establishment of governments around the world. After that, we examine the potential devolution of the central importance of the Declaration in our current environment as some of its founding principles are being ignored, constrained, or contradicted.]

The Declaration of Independence united the thirteen colonies/states in the revolutionary war for independence from Great Britain and the monarchial rule of King George III. As we noted in our earlier blog, if the United States had not won that war, the Declaration would have been no more than words on parchment.

Evolution

The hard-won victory made the Declaration a foundational document, and provided the basis for evolution from war to two historical American pivot points: Drafting of the U.S. Constitution, and adding the Bill of Rights as the first ten amendments to the Constitution.

In 1786, a decade after the Declaration of Independence was signed, the United States and many of the states were bankrupt. This was attributable primarily to the fact that the Articles of Confederation adopted in 1777 created a weak form of federal government, gave Congress virtually no power to regulate domestic affairs, and absolutely no power to tax or regulate commerce.

Because of this and other problems, in 1787 the Continental Congress called for a Constitutional Convention “to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them to be necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the union.”

On May 25, 1787, The Constitutional Convention convened in Philadelphia with 55 delegates from 12 states (Rhode Island, which opposed the Constitution, sent no delegates). The delegates debated for three months over two competing plans:

- The Virginia Plan, calling for a strong national government, with both branches of the government apportioned based on population, and

- The New Jersey Plan, which kept federal powers quite limited and maintained the Continental Congress.

Compromises were reached during those three months including: Giving the new Congress the power to regulate commerce, currency, and the national defense; representation in the House of Representatives, to be based on population; and two senators from each state in the new Senate.

On September 17, 1787, the Constitution was voted on. 39 out of the 55 delegates supported adoption — barely enough for it to be approved by the delegates in attendance.

Getting the Constitution approved in Philadelphia was the easy part. Getting it ratified by the states was more difficult.

During the debates in the states, between 1787 to 1790, on ratifying the constitution, many citizens expressed concern that it gave far too much power to the central government, would result in tyrannical rule, and provided no protection for their civil rights. So they demanded amendments guaranteeing those rights be added to the document.

Based upon that feedback, on September 15, 1789, the first Congress of the United States proposed 12 amendments to the Constitution. The first two, relating to the number of representatives and their compensation, did not pass. Amendments 3–12 did. Those 10 amendments became known as the Bill of Rights. Four deal with asserting or retaining affirmative rights (e.g., freedom of speech). Six dealt with protection against negative actions the government might take (e.g., protection against excessive bail and cruel and unusual punishment).

Even with the addition of the Bill of Rights, getting the Constitution ratified by the states was no slam dunk. It just squeaked by in some states. The legislative vote in Virginia was 87 for and 79 against. Rhode Island was the last of the 13 states to ratify the Constitution, on May 29, 1790, by the closest vote, 34 for and 32 against, after it lost overwhelmingly in a popular referendum there in March 1788, by a vote of 237 for and 2,708 against.

The U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights provided the framework to put a functional national government in place to transform the rhetoric in the Declaration of Independence into an operational reality. That government of three branches (legislative, executive, and judicial) was structured to provide an effective system of checks and balances to ensure there was no monarchial or tyrannical rule in the U.S. It was also designed to elevate and ensure the rights of citizens and states were protected.

As this discussion has shown, putting that government in place was an evolutionary process. It did not happen overnight.

Together, the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights have shaped and influenced the evolution of this nation and the slow forward progress of its citizens over the 250 years since this country’s founding.

Jeffrey Rosen and David Rubenstein, end their essay for an exhibit at the National Constitution Center by stating:

The Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights are the three most important documents in American history because they express the ideals that define “We the People of the United States” and inspire free people around the world.

The impact of the Declaration on people around the world has not been quite the same as it has been on people here in the United States. David Armitage, professor of history at Harvard University, points this out in his essay for the National Constitution Center, in which he provides a number of observations, including the following:

Most Americans have seen the Declaration as a charter of their individual rights to “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” By contrast, most of those outside the U.S. have taken it to be a charter of their collective rights to form “one People,” to revolt against external authorities, to secede from empires, and ultimately form independent states.

Since 1776, there have been hundreds of declarations of independence issued around the world, most ignored, but many successful in securing independence — that is, recognized statehood — for a people or nation breaking away from another authority. Over half of the states now represented at the United Nations have a foundational document they call a declaration of independence or something similar.

Few of these modern declarations borrowed the Declaration’s language of individual rights.

The United Nations itself, however, does have a Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which it adopted in 1948 after the end of World War II. Article I of the U.N. Declaration states: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” Article II begins as follows:

Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.

The Declaration of Independence has had an evolutionary journey around the world. In A History of the Declaration of the Independence, the National Archives, which has housed the Declaration since 1952, reports the Declaration has made its own journey, here in the United States, through the centuries, since its publication on parchment in 1776. According to the National Archives:

Chronologically, it is helpful to divide the history of the Declaration after its signing into five main periods, some more distinct than others. The first period consists of the early travels of the parchment and lasts until 1814. The second period relates to the long sojourn of the Declaration in Washington, DC, from 1814 until its brief return to Philadelphia for the 1876 Centennial. The third period covers the years 1877–1921, a period marked by increasing concern for the deterioration of the document and the need for a fitting and permanent Washington home. Except for an interlude during World War II, the fourth and fifth periods cover the time the Declaration rested in the Library of Congress from 1921 to 1952 and in the National Archives from 1952 to the present.

Devolution?

The Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, known collectively as the Charters of Freedom, are housed together in the Rotunda of the National Archives building in Washington, D.C. In 2026, given developments under the current administration, we must wonder if the freedoms promised in those charters, which have already diminished, are at risk of disappearing.

The No Kings protests by millions of citizens last year in June, on Donald Trump’s birthday, and later in October, highlighted the concerns regarding the monarchical behavior of Trump during his second term in office. In February, Trump referred to himself as “the king” in a Truth Social posting after he had eliminated a congestion pricing fee of $9 for cars to enter New York City in Manhattan below 60th Street, writing:

CONGESTION PRICING IS DEAD. Manhattan, and all of New York, is SAVED. “LONG LIVE THE KING!”

The White House followed up that posting by issuing a picture of Trump wearing a crown on a magazine cover, with the words Long Live the King alongside him.

This might have been an attempt at humor. Given the majestical manner in which Trump governed since re-entering the White House, however, it cannot be.

As the supreme ruler of these Divided States of America, he has sought to strip away and/or abolish many of the courses charted in the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

In terms of the Declaration, Trump in 2026, and since assuming the presidency in 2025, has engaged in activities and actions similar to those that were cited as justification for the separation from Great Britain in 1776. Consider the following “Facts to be submitted to a candid world” drawn from the Declaration:

- “He has endeavored to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.”

- “He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.”

- “He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.”

- “He has affected to render the military independent of and superior to the Civil power.”

- “For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:”

- “For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:”

- “For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offenses”

Under Trump’s leadership this time round, the unalienable right of the pursuit of happiness appears to have become more difficult. The 2025 Gallup World Happiness Report showed the U.S. ranked 24th in the world — its lowest ranking ever.

In terms of the Constitution, Trump has been equivocal in speaking about it, but unequivocal in taking actions contrary to it.

In 2017, during his first term in office, he issued a statement saying “As President, my highest duty is to defend the American people and the Constitution of the United States of America.” In 2022, after he lost the 2020 election to Joe Biden, which he falsely claimed was stolen, he posted on Truth Social: “A Massive Fraud of this type and magnitude allows for the termination of all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution.” In May 2025, during an interview on NBC’s Meet the Press, Kristen Welker asked him if he needed to uphold the Constitution. His response was “I don’t know.”

Trump went on to say that “I have brilliant lawyers that work for me, and they are going to obviously follow what the Supreme Court said.” That is what Trump said. But as always, what he says is not necessarily what he does.

Trump’s actions speak louder than his words. They say that the Constitution is immaterial to him. What is relevant is what he wants to do, and wants done, and to have absolute control over everything and everyone.

The most egregious example of this is what Trump has done with the three branches of government. As president, Trump has operationalized the unitary executive theory, saying all departments in the executive branch are subservient to his will alone, and neither the Congress nor anyone else can interfere with him. He has also asserted control over independent agencies, such as the Federal Trade Commission and the Security Exchange Commission, and made them part of his domain.

With Michael Johnson as Trump’s Speaker of the House, Republican representatives were instructed not to come to work during the governmental shutdown, and they stayed away from Capitol Hill for nearly two months. Even if they had come to work, they would have gotten very little done.

Finally, there is the Supreme Court, which has become not an independent branch, but a branch aligned with the Executive Branch. It’s the Court that gave Trump immunity for virtually anything he does while in office, so he can issue hundreds of executive orders, and govern with impunity, because he has immunity.

As we stated in an earlier blog:

In 2025, with the Congress controlled by the Trump administration and the Supreme Court collaborating with the Trump administration, it may not be an overstatement to say there may no longer be three equal branches of government. Today, there may only be one branch. It might be labeled the unified branch of the Supreme Ruler.

A second example of Trump’s destructive actions is the devastation his administration has wrought on the federal government. Elaine Kamarck provides an excellent analysis of the nature, and potential long-term consequences, of that devastation in her November 21, 2025 Brookings Institution research article, which begins as follows:

It has been 10 months since Donald Trump was inaugurated as president for his second term. In this period, the federal government has experienced an unprecedented number of cuts to the workforce. These reductions have come rapidly, often in defiance of existing laws, regulations, and norms, leading to a . significant number of lawsuits

While the cuts are still being litigated, another more immediate question has arisen: Can the government continue to operate with a greatly reduced workforce, or will it fail to deliver essential services in ways that negatively affect ordinary Americans?

Kamarck highlights in her article that the Trump regime’s erratic approach has led to: several agencies firing and rehiring employees in agencies, such as the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Energy; hundreds of thousands of “voluntary leaves”; hiring new workers in some agencies, such as the Federal Aviation Administration and the Department of Homeland Security; advertising jobs but not filling them.

She concludes her analysis by stating, “As Harry Truman famously said in reference to the office of the president, ‘The buck stops here.’ One of Trumpʼs ultimate legacies will be whether a downsized government leads to catastrophic breakdowns or increased efficiency.”

Another Trump legacy will be the wrongs his administration has done to the Bill of Rights. As the first ten amendments to the Constitution, the Bill of Rights amplified the “unalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” promised in the preamble to the Declaration of Independence.

Although those rights were added to the Constitution in 1789, they were not immediately available to many citizens until much later when additional amendments:

- Abolished slavery (XII -1865);

- Gave birthright citizenship (XIV-1868);

- Gave the right to vote regardless of race or color (XV — 1870):

- Gave women the right to vote (XIX -1920);

- Eliminated the payment of poll taxes as a requirement to vote (XXIV — 1964);

- Gave 18 year-olds the right to vote (XXVI — 1971).

The extension of these civil rights has been definitely an evolutionary process taking centuries. By contrast, Trump’s reduction or restrictions of these rights has been a series of attacks and actions taking place in one year.

Numerous organizations, including The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, the American Civil Liberties Union, and Amnesty International have commented and provided detailed information on the scope and nature of those actions.

The Brennan Center for Justice observes:

Many of these actions are compromising the federal government’s ability to provide the basic services that keep the country safe and prosperous. They are also undercutting individual rights and civil liberties.

Possibly the most devastating of these actions are those being taken by ICE and the U.S. military as part of the administration’s mass deportation of “illegal immigrants.”

The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution states:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath and affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.

The Ninth Amendment states:

The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

The manner in which ICE’s (the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s) agenda has been implemented effectively expunges those amendments from the Bill of Rights.

As we stated at the beginning of this blog, drafting the Constitution and adding the Bill or Rights were historical pivot points for our nation. We define a pivot point as an area that must be leveraged and addressed effectively in order to effectuate change and achieve positive outcomes.

Pivot points define the character and shape the destiny of a nation and its people. They establish the rules of the game and influence the attitude of the public. They create an upward or downward trajectory, and accelerate or decelerate forward movement and progress.

Today, due to President Trump and his administration’s initiatives, which are negating or reversing elements of the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, we are at a major pivot point. How this situation is resolved will determine whether this nation remains a democracy or becomes an autocracy.

In 1776, the signers of the Declaration of Independence understood it was their responsibility to speak out against “a history or repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States and to put a government in place that “derives its just powers from the consent of the governed.”

In 1796, in his farewell address, President George Washington warned us to be careful, writing:

It is important, likewise, that the habits of thinking in a free Country should inspire caution in those entrusted with its administration, to confine themselves within their respective Constitutional spheres; avoiding in the exercise of the Powers of one department to encroach upon another. The spirit of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers of all the departments in one, and thus to create whatever the form of government, a real despotism.

In 2026, it is essential for concerned citizens to understand our responsibilities as the signers of Declaration did, and to heed the words of President Washington.

If this democracy is to survive and to thrive, there need not be a revolutionary war, but there must be a united front to end the devolutionary war that Trump has launched, with a victory not for a unitary leader, or those who would divide us, but for we, the people working together to create a more perfect union for all.