Poor No More

![]() By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, August 12, 2018

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, August 12, 2018

Are there no more poor people in the United States of America?

That’s what the following statement in the report, Expanding Work Requirements in Non-Cash Welfare Programs (Expanding Work Requirements Report), recently released by the White House Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) implies:

“Based on historical standards of material well-being and the terms of engagement, our War on Poverty is largely over and a success.”

Is that assertion correct? Have the poor disappeared?

No. But this White House, and many in the Republican Party, want them to. That is why they are declaring victory in the War on Poverty, and replacing it with a war on those in poverty.

Let’s examine this shift by looking at:

- The state of poverty in the U.S.

- The public’s attitude regarding those in poverty

- The administration’s approach to poverty

- Whether there is a better way to address the poverty problem

The State of Poverty in the U.S.

What percent of the American people are in poverty? It depends on what measure one is looking at and where one is looking

Based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2016 estimates, the official poverty ratewas 12.7 percent (43.1 million Americans). The supplemental measure, which takes other factors such as family size and age of the household into account, raises that to 14 percent (45 million).

The Census Bureau defines “deep poverty” as living in a household with total cash income below 50% of its poverty threshold. The rate for those in that condition was 5.8 percent (18.5 million people) — over 45 percent of those in poverty.

In their article for the Washington Post, Karen Dolan, a Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, and William J. Barber II, co-chair of the Poor Peoples Campaign, observe that “Almost 100 million more live at 200 percent of the poverty line, a more accurate indicator of a family’s ability to make ends meet.” Dolan and Barber estimate that “around 43 percent of Americans are poor or low income.”

Drawing upon new data just available from the World Bank, in an article for the New York Times, Angus Deaton, 2015 Nobel laureate in economics, finds that there are 5.3 million Americans “who are absolutely poor by global standards” — living on $4 a day. Deaton comments, “There are millions of Americans whose suffering, through material poverty and poor health, is as bad or worse than that of poor people in Africa or in Asia.”

No matter which of the foregoing measures that an objective observer chooses to use regarding poverty in the U.S., it would be difficult to conclude that the “War on Poverty is over and a success.” Can you say “mission accomplished?”

The truth is, as the Center for Poverty Research at the University of California, Davis, points out: “Since its initial rapid decline after 1964 with the launch of major War on Poverty programs, the poverty rate has fluctuated between around 11 and 15 percent.”

Given this, the War on Poverty is — and should still be — a work in progress. The question becomes why is it set aside? In part, the answer is undoubtedly the public’s changing attitudes regarding those in poverty.

The Public’s Attitude on the Impoverished

The American public is not of one mind on those in poverty. As we pointed out in a blog we posted in 2014, there was a growing “compassion gap” toward those in need between Democrats (D) and Republicans (R).

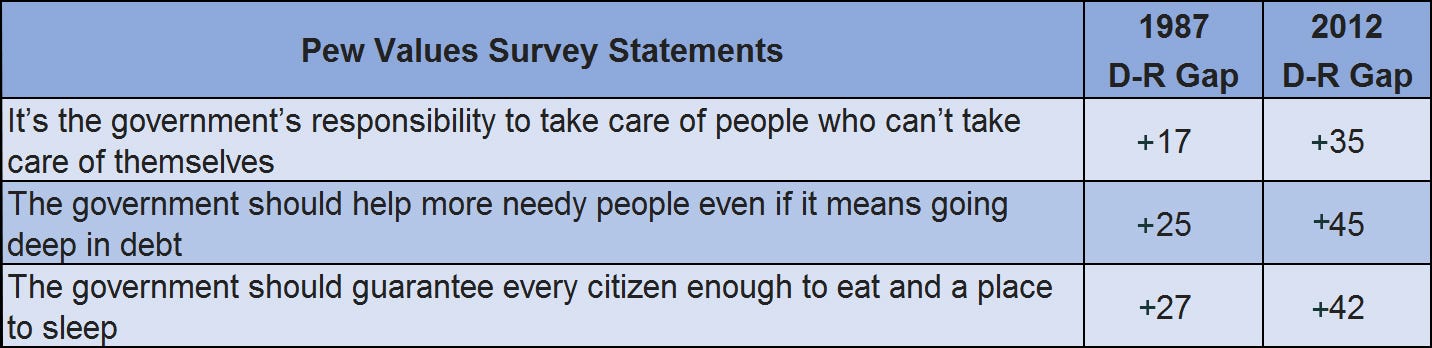

At that time, we drew upon the values survey done by the Pew Research Center to show the following differences between D’s and R’s between the 1987 survey results on support for the social safety net and those for 2012:

Pew has not updated its values survey since 2012. If it had, however, we expect that with the populist movement and the “Trumpetization” of the Republican Party, the compassion gap would have become a chasm.

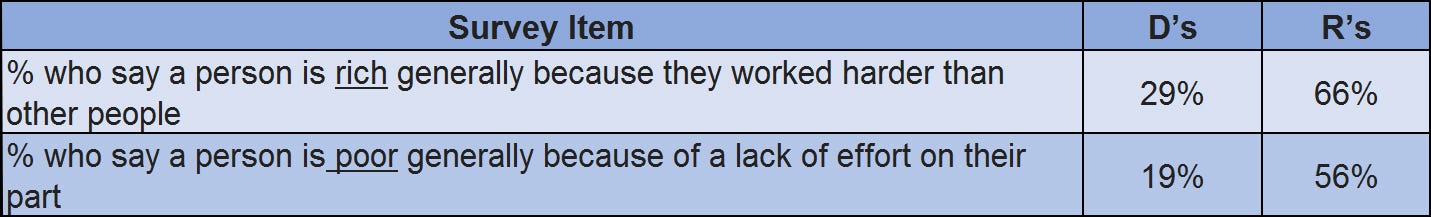

The Pew Center did do a survey in 2017 asking respondents why a person is rich and why a person is poor. The comparative results of D’s vs R’s on this survey are presented in the table below:

The bottom line is Republicans, in general, have much different perceptions and attitudes regarding and assistance to the poor than Democrats.

The Administration’s Approach to Poverty

That is why now that the Trump administration is in power, and the Republicans control both the House and the Senate, it was inevitable that this work requirements solution would be implemented. It is completely consistent with the ideological, philosophical, and personal viewpoints of the bulk of their political supporters.

The work requirements approach singles out what might be called “the undeserving poor”, i.e., non-disabled working age adults (between 18 and 64). According to the Expanding Work Requirements Report, those individuals as of December 13 constituted “the majority of adult recipients on Medicaid (61 percent), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (67 percent), and rental housing assistance programs (59 percent).”

In total, that’s a very high percentage of “working age adults” in this segment of the poverty population. There is undoubtedly a need and there should be programs to help these adults establish themselves and escape from the non-cash welfare rolls.

There are many problems, however, with a mandatory requirement as the means to that end. They include: is there work available for these adults? Are they qualified for the work that is available? Does getting work in low-paying jobs eliminate their need for any type of assistance? Are there reasons outside of not being disabled that they are not working? Does a work requirement lead to gainful employment with opportunities for advancement over time? And is this requirement the best approach for dealing with America’s poverty problem?

The Report, even though it is lengthy, cites some studies, and is well-footnoted, provides scant evidence on most of these concerns. Instead, it presents three primary reasons for expanding work requirements:

- The safety net transfer polices (both cash and non cash) have reduced poverty but the “policies have been accompanied by a decline in self-sufficiency (in terms of receipt of welfare benefits).”

- An alternative solution, such as increasing the Earned Income Tax Benefit, “could exacerbate already high implicit taxes on low-skill part-time workers.”

- Evidence suggests “work requirements can improve outcomes for recipients” and “may improve child well-being.”

These reasons, with the definition of “self-sufficiency” and the use of qualifiers such as “can” and “may” instead of “will,” along with the data supporting them, are neither compelling nor persuasive. They do, on the other hand, display the real intent of the work requirements, which is to move these “non-disabled working age adults” — deadbeats and freeloaders, if you will — off the welfare rolls

The belief is that work, in and of itself, itself is the answer to the poverty problem. That is absolutely and unequivocally not the case.

Eduardo Porter made this clear, eloquently and movingly, in a New York Times article. Commenting on the “welfare to work” program initiated during Bill Clinton’s second term in office, Porter observed:

“Work requirements did of course, encourage the mostly poor single mothers of able body and mind who did not already hold a job to get one. Their earnings from work increased. Welfare rolls, government spending on welfare payments declined.

But what did not happen is perhaps more important: The incomes of all the mothers ostensibly freed from dependence hardly rose at all. The loss of welfare payments pretty much canceled out their earnings from work. With little education and virtually no access to training, they got stuck in the low-wage labor market that has taken over so much of the American economy.”

This 21st century work requirements initiative reflects the values of the Republican Party, but it brings nothing new of value to the table for those in poverty to break the vicious cycle in which they are trapped.

That’s the bad news. The good news is there is a better approach that could be implemented if Washington, D.C. could ever move beyond the partisan gridlock that has consumed and paralyzed it for over a decade now.

A Better Way to Address the Poverty Problem

The better way is a comprehensive approach presented by the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and the left-leaning Brookings Institution (Brookings), in a report titled Opportunity, Responsibility, and Security: A Consensus Plan for Reducing Poverty and Restoring the American Dream (Consensus Plan) in December of 2015. We commented on the plan in a blog shortly after it came out.

Here is some of what we had to say:

“The Consensus Plan is a serious and significant document. It was jointly crafted by a Working Group on Poverty and Opportunity of 15 representatives.

What makes the document serious is that there is a detailed substantive analysis of the issue of poverty in the United States today and the conditions of the poor. What makes it significant is that its recommendations were achieved by building consensus, which required trade-offs and compromise

The Consensus Plan provides recommendations in “three domains of life that interlock so tightly that they must be studied and improved together: family, work and education.”

Recommendations in the family domain include: promoting parenthood, marriage and two-parent families; delayed responsible childbearing (including support for contraception); and increased parenting education.

Recommendations in the work domain include: improving skills to get well-paying jobs; making work pay more for the less educated (including raising the minimum wage, but not to the $10.10/hr proposed by President Obama); and raising work levels of the less well-educated (including requiring those who are capable and receiving benefits to seek employment).

Recommendations in the education domain include: increased public investment in underfunded stages of education (including preschool); educating the whole child (including socio-emotional and character- building); and modernizing the organization and accountability of education (including supporting charter schools and focusing more attention on the performance of community colleges).”

Even though we felt that the Consensus Plan was an excellent document, we were skeptical about its being used by either candidate in crafting their approach to the poverty problem. We opined:

“We believe that selective elements in the Report could find some support “across the political spectrum”. But, we do not think that it will receive much — if any — support in its entirety as an approach for “going to war” on poverty.”

Our reasoning for this is simple. The plan was built through consensus. And, as such does not align to the ideological biases and blinders of either the right or the left.

In 2018, we are saddened that our assessment and prediction was correct. We cannot say for certain what Hillary Clinton would have done if she had gotten to the White House as President.

We do know for certain what President Trump has done. There is no one and nothing there to fight the war on poverty.

The poor in America deserve a fighting chance. The Consensus Plan would have given them that.

The poor will still be here and in poverty after the administration’s Working Requirements approach fails. Our fondest hope and desire is that in 2020, the Consensus Plan will be dusted off and used to transcend ideological and political boundaries in order to continue the War on Poverty until it can truly and honestly be proclaimed “over and a success.”