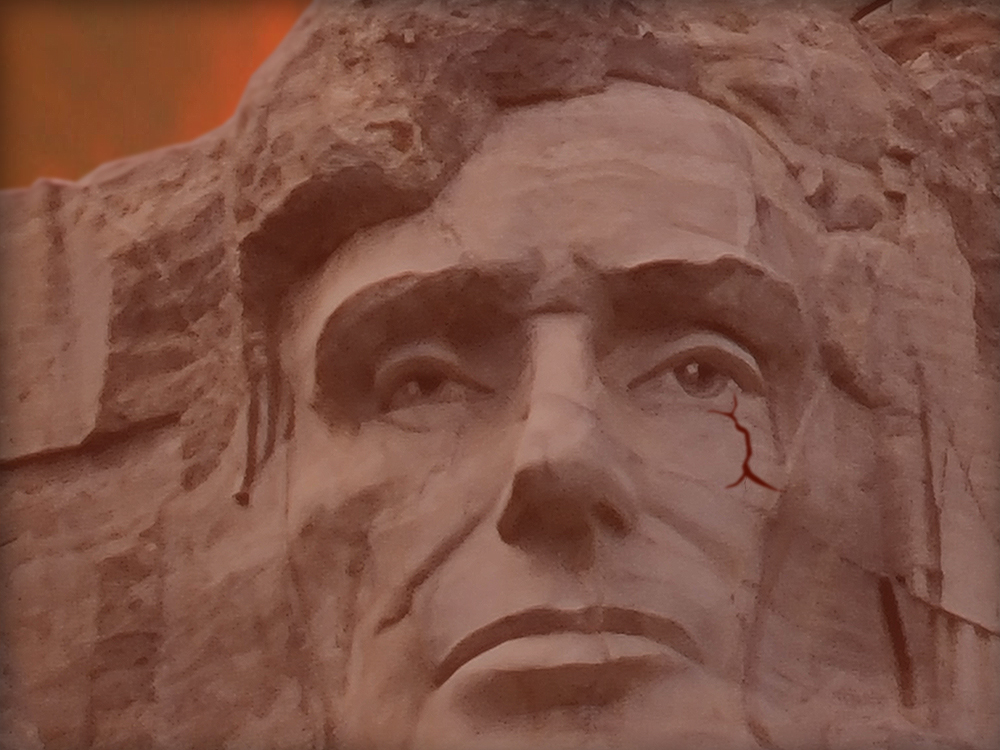

Our Fragmenting Democracy

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, June 14, 2022 (Image credits: Tom de Boor)

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, June 14, 2022 (Image credits: Tom de Boor)

The democratic republic known as the United States of America is fragmenting.

The storming of our U.S. Capitol by insurrectionists on January 6, 2021 highlighted elements and some of the consequences of this fragmentation. The January 6 Committee, in its series of eight hearings, which began on June 9, is providing new and important insights into what caused and who precipitated and contributed to that assault.

Unfortunately, however, January 6 is only the tip of the fragmentation iceberg, and information on its sources will not tell the whole story of nor end the fragmentation. More needs to be known to accomplish that. Fortunately, the full extent and nature of this breaking apart is being documented in everything from cartoons to opinion pieces and research studies.

The comic strip B.C., created by Johnny Hart, regularly features commentary by cavemen on issues of relevance today. In a recent cartoon, in panel one, a caveman walks up to another caveman standing behind a rock which is labeled, Mr. Kno-It-All. The caveman asks Mr. Kno-It-All, “What do you get when you mix a country divided along political lines with loss of institutional trust?” In panel 2, Mr. Kno-It-All responds: “Two countries.”

While that cartoon can be viewed as accurate but humorous, George Packer’s article, “How America Fractured Into Four Parts,” published by The Atlantic in its July/August 2021 issue, and Perry Bacon, Jr.’s op-ed, “The U.S. has four political parties stuffed into a two-party system,” published by The Washington Post on March 8, 2022 ,are also accurate. But they are not funny.

Packer summarizes his description of the Four Americas (Free America. Smart America. Real America. Just America.) and the problem they create in our current environment as follows:

All four of the narratives I’ve described emerged from America’s failure to sustain and enlarge the middle-class democracy of the postwar years. They all respond to real problems. Each offers a value that the others need and lacks ones that the others have.

Free America celebrates the energy of the unencumbered individual. Smart America respects intelligence and welcomes change. Real America commits itself to a place and has a sense of limits. Just America demands a confrontation with what the others want to avoid.

They rise from a single society, and even in one as polarized as ours they continually shape, absorb, and morph into one another. But their tendency is also to divide us, pitting tribe against tribe. These divisions impoverish each narrative into a cramped and ever more extreme version of itself.

The Four parties that Bacon sees are, on the Republican side: Trump Republicans and the Old Guard. The Old Guard splits into those who are more traditionally conservative, such as Senator Mitch McConnell (R-KY), and those who are anti-Trump, such as Senator Mitt Romney (R-UT). On the Democratic side: The Center Left, which includes those such as President Joe Biden and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and The Left-Left, which includes Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY).

Bacon views this four-party structure as a problem for three reasons: It empowers Trump Republicans. It creates a great tension and divide within the Democratic Party. It disenfranchises the anti-Trump Republicans and independents who don’t fit easily into one of the four groups.

So, is the American democracy breaking into 2 or into 4? New research suggests that it may be fragmenting into many more parts than that.

In March, Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement (PACE) released the results of a Language Perceptions Survey of “terms and phrases commonly used in democracy and civic engagement work,” which captures the dimensions of that fragmentation. The PACE study was conducted in November 2021 by Citizen Data, through a nationwide online sample of 5,000 respondents, to “understand people’s familiarity with a variety of common terms as well as emotions and gut reactions associated with them.”

The survey consisted of 21 terms. The top five most positively rated terms across all demographics were: unity, liberty, citizen, justice, and democracy. The top five most negatively rated terms were: privilege, social justice, racial equity, activism, and justice.

Importantly, the research disclosed that there were distinctive differences in positivity ratings by age, race, sex, class, education, socio-economic class, and political affiliation. For example, as indicated below, those in the 18–34 age cohort, Blacks, females, and those with less education were much less positive in their ratings on selected words highlighted in the Executive Summary of the survey:

- For patriotism, the positive ratings for the 18–34 years of age was 35% versus 77% for those 65 and over.

- For patriotism, the positive ratings for Blacks was 33% versus 72% for Whites.

- For democracy, the positive ratings for females was 55% versus 68% for males.

- For democracy, the positive ratings for those with a high school education or less was 47% versus 72% for those with a bachelor’s degree.

In his analysis of the PACE survey data for The Bulwark, Theodore Johnson, a writer for The Bulwark and the director of the Fellows Program at the Brennan Center for Justice points out: “…black Americans are nearly 50 percent more likely to think positively of social justice and activism as white Americans; Democrats twice as likely as Republicans.”

Johnson concludes,

In America, democracy is more than just a system of institutions, relationships and processes. It is a declaration of our national identity that we have not yet managed to accept and appreciate as being multiracial and ideologically diverse.

So when you hear laments about the state of our democracy, don’t think exclusively in terms of a crumbling system. Think instead of a people who are hesitant to be governed by those different than them, a nation deficient in social trust.

Johnson’s insights are valid. We need to think seriously about this hesitancy and what we the people can do to create more “social trust” among the citizenry. We must also recognize, however, that there are many citizens who would not try to repair the “crumbling system,” but to use the fragmentation as a reason to make it irreparable.

Thomas B. Edsall addresses this dilemma in some detail in his April 13 New York Times guest essay titled, “Trump poses a Test Democracy is Failing.” Edsall opens that essay as follows:

Ordinary citizens play a critical role in maintaining democracy. They refuse to re-elect — at least in theory — politicians who abuse their power, break the rules and reject the outcomes of elections they lose. How is it, then, that Donald Trump, who has defied these basic presumptions, stands a reasonable chance of winning a second term in 2024?

Edsall draws upon insights from a group of political scientists and public policy experts to answer that question. The answer from all is similar. Many citizens put politicians, party, and their own personal priorities above the interests of the country and democratic values.

According to Edsall, Matthew Svolik, a Yale political scientist, and Matthew H. Graham, a postdoctoral researcher at George Washington University, “…have calculated that ‘only 3.5 percent of voters realistically punish violations of democratic principles in one of the world’s oldest democracies.’”

In an email to Edsall, Robert C. Lieberman, political scientist at John Hopkins University, states:

The perception among many white Americans that their status at the top of the political hierarchy is eroding is certainly a critical factor fueling the crisis of American democracy today. This is a recurring pattern in American history; when proponents of expanded and more diverse democracy gain power those who have a stake in old hierarchies and patterns of exclusion are often willing to defy democratic norms and practices in order to stay in power.

Since Trump’s election defeat in 2020, and the subsequent and continuing refusal to accept or acknowledge it, the plot has thickened. As Edsall comments, “The efforts by Republicans to take over control of elections through state laws giving local legislatures the power to overturn elections results — as well as by running candidates for secretary of state who espouse the view the 2020 election was stolen — are troubling to say the least.”

Donald Moynihan, a professor of public policy at Georgetown University, agrees, weighing in an email to Edsall saying that he is “more worried about declines in democracy by formal changes in the law than by events like January 6th.”

This perversion of the electoral legal structure is made more dangerous by the fact that, as Edsall states in his piece, “Partisan polarization has pushed Americans not only into mutually exclusive political parties, but also into two warring civic cultures.’ This brings us back to the lack of “social trust.”

In our January 2, 2020 blog, we named “trust” our word of the year for 2019. As we explained in its opening, “We select trust not because of its presence but because of its absence … In the year 2019, trust was absent on almost all fronts, including in the president; in government; in institutions, in the free press; and most problematically, in each other.”

In that blog, we reviewed some of the findings that the Pew Research Center began publishing, beginning in April of 2018, in more than 30 pieces on its research on trust, facts, and democracy. A Pew study released in October 2019 disclosed that Democrats and Republicans did manage to agree on one thing –that is they can’t agree. 73% of those partisans surveyed said, “On important issues facing the country, most Republican voters and Democratic voters not only disagree over plans and policies, but also cannot agree on basic facts.”

That same study showed that “75% of the Democrats surveyed said Republicans are more close-minded than most Americans. 63% of the Republicans are more unpatriotic than most Americans.”

This separation is significant. Given this difference of opinions and feelings by political party and, as described earlier in this piece, among segments of the American people, what can be done to bridge the gap and re-cement our fragmenting relationships?

Much has been written lately on this topic. Three well-known experts on democracy, social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, economist Thomas Piketty, and political scientist Yascha Mounk have produced interesting analyses.

Haidt, in a May Atlantic article, attributes much of our current civic dissonance and dissolution to abuse through the social media. He closes his article by noting,

In recent years Americans have started hundreds of groups and organizations dedicated to building trust and friendship across the political divide, including Bridge USA, Braver Angels (on whose board I serve), and many others listed at Bridge Alliance.us. We cannot expect Congress and tech companies to save us. We must change ourselves and our communities.

Piketty, in his new book, A Brief History of Equality, published in April, argues we are already on the right path towards greater equality and sharing for all Americans. In an interview with David Marchese for the New York Times Magazine, Piketty asserts:

Let me put this clearly: I understand that each year and each decade is tremendously important, but it’s also important not to forget about the general evolution. We have become much more equal societies in terms of political equality, economic equality, social equality as compared with 100 years ago, 200 years ago. This movement began with the French and U.S. revolutions. I think it is going to continue.

Piketty acknowledges that there are some factors that stand in the way of the evolution, such as some democratic institutions being less democratic than they should be, but believes we will stay the course. The one thing we need to do, in his opinion, is to tax the wealthy. (A recommendation we must observe which is much easier said than done given the current composition of two of our democratic institutions — the U.S. Congress and the Supreme Court.)

Mounk has a new book, The Great Experiment: Why Diverse Democracies Fall Apart and How They Can Endure. In an April 19 Atlantic article, based upon an excerpt from the book, Mounk stresses three kinds of limits on state power have evolved: regular elections, the separation of powers, and protection of individual rights to maintain diverse democracies.

He opines that elections and separation of powers are insufficient, and that the key to successful continuation of ‘the great experiment” is a system that protects individual rights. Mounk ends his article by asserting:

Citizens need to benefit from all the institutional innovations that have historically proved capable of keeping a tyrannical state at bay and know that the communities to which they belong will be able to practice their customs in peace. And they must also be able to call upon the assistance of the state to defend them against any private groups that might, against their will enclose them in a cage of norms. Only a diverse democracy built on the principles of philosophical liberalism is capable of protecting both of these core values at the same time.

Haidt, Piketty, and Mounk each provide worthwhile perspectives. In our opinion, to make them most valuable as references to consider for working toward a solution to reduce America’s current fragmentation, there is a short term and long-term need.

The short-term need is to recognize that our diverse American democracy is at a precipice today, and it is essential to take the action necessary within the next few years to prevent what has fragmented from fracturing and falling apart. The long-term need is to recognize that a “near term” win for democracy does not ensure continuous forward progress. That requires doing a better job in preparing future generations to appreciate, support, and collaborate in contributing to the positive evolution of this democracy in the decades to come in this 21st century.

We have addressed both of those needs in earlier blogs. At the beginning of this year, we posted a blog titled the “Island States of America: Is that this country’s future?”

Early in that blog, we stated “Events in 2021 show that states rights are becoming dominant in this country’s system of governance and the nation is becoming increasingly balkanized.”

We explained that there were historical underpinnings for this movement but attributed the current conditions to Donald Trump, his allies and loyal supporters, declaring:

At the outset of the Trump presidency, the United States was in a nearly apocalyptic state.

Trump’s island states approach to governing for four years, followed by the refusal to accept the results of a legitimate election and allow the peaceful transfer of power, combined with the continued perpetuation of the Big Lie, have made the current state of this nation much more apocalyptic than it was nearly five years ago.

If the current course we are on is not changed in the near future, there will most probably continue to be a United States of America, but it will be united in name only.

After describing this perilous situation, we set out the following three key ingredients required to change that course:

- A national leader with a compelling vision and cross-cutting appeal and support

- 21st century citizens who are American patriots and community builders who view the current division with alarm and are willing to come together to build the nation’s social capital and the common good.

- A unity agenda around which citizens can rally in order to reinforce, faith, confidence at competence in government at all levels.

This democracy cannot afford four more years of a Trump presidency or of a mirror image and likeness president with a similarly divisive disposition.

We are in a critical race. It is not a race to the finish. It is a race for the future. It is a race that will determine the fate of the nation.

Winning that race in the sprint over the next four years is just the starting point. The real win must come with future generations in the marathon in the decades to come.

As we have noted before, one of the underlying sources for the dissatisfaction of the current generation is a basic lack of knowledge regarding the functions, operations, and positive contributions of government to the American way of life.

Students going to middle school and high school in the last half of the twentieth century likely had some classroom exposure and requirements in civics/government/U.S. history. Beginning in the first decade of the twenty-first century until today, however, with the increasing emphasis placed on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math), and with the significant decrease in educational funding for civics across the nation, this is no longer the case. The federal government currently spends approximately $50 per student on STEM education versus 5 cents per student on civic education.

A comprehensive ongoing approach comprised of three components should be implemented to redress this educational mis-emphasis:

- Prepare future generations of citizens by beginning the teaching of civics and civic engagement in middle school. Educational research suggests that formation of a positive orientation toward an area earlier in a student’s career, which would be in the later elementary (4th and 5th grade) and middle school years, increases the potential for sustained interest and participation.

- Enhance online civic reasoning competence at all levels (middle school, high school and college. In a world in which social media dominates communication — especially for our youth — fake news represents an existential crisis for this country. It must be controlled. The best way that can be accomplished is through informed and knowledgeable consumers who can differentiate fiction from fact.

- Require mandatory national service. National service provides the basis for sharing and potentially bridging our divides. In the United States today, service is somebody else’s business. We need to make it the nation’s business — service to our country and fellow citizens. That is the measure of true patriotism.

The PACE survey documented the importance of civic knowledge and civic engagement for ensuring positive attitudes towards and participation in our American democracy. The respondents who had a civics or history class in that survey were much more positive in their ratings of common civics-related terms such as liberty, democracy, common ground, citizen, and civility. Those who took civics classes were also more likely to vote in the November general election with 65% participating compared to 50% of those who did not take civics classes.

In 1820, Thomas Jefferson cautioned the citizens of a very young American democracy, “I know no safe depository of the ultimate powers of the society but the people themselves; and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them but to inform their discretion.”

Slightly more two centuries later in 2022, the United States of America is fragmenting into 2, 4, 50 and many, many more individual and separatist pieces. In these polarized times, it is essential to enlighten and inform our citizens so that they can exercise their wholesome discretion to preserve our democracy and to make it fairer, better, and stronger for all in the future.