Orientations And Rulings

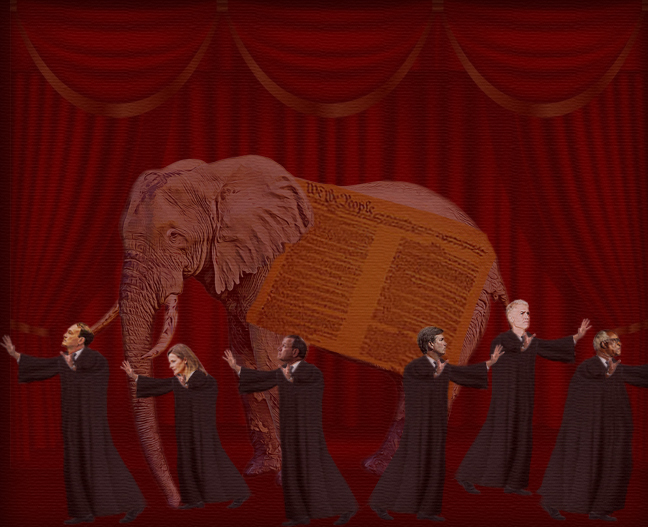

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, April 11, 2024 (Image credits: Tom de Boor, Adobe, Dreamstime, et al)

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, April 11, 2024 (Image credits: Tom de Boor, Adobe, Dreamstime, et al)

Our federal judicial system was designed to be a place where decisions could be reached and rulings could be made in an objective and nonpartisan manner. Recent rulings, commentary, and research indicates this is not happening. In fact, the composition of a court and the political orientation of the judges have a substantial impact on a court’s rulings.

Supreme Court Decisions and Rulings

We have been writing about the Supreme Court’s Republican conservative membership and rulings for some time. In July 2022, after the Court overturned Roe v. Wade, we provided the following analysis:

The five members of the conservative majority, in order of seniority on the court, are: Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett. Thomas, Alito, Kavanaugh, and Barrett are Catholic. Gorsuch is Episcopalian but was raised Catholic.

Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett were all appointed to the court by President Trump. During his campaign for the presidency in 2016, Trump promised to appoint justices who would overturn Roe v. Wade. These were his candidates for accomplishing that.

In his February 26 article for the New York Times, Jesse Wegman of the Times editorial board was harshly critical of the impact of this conservative majority on the court. In his piece titled, “The Crisis in Teaching Constitutional Law,” Wegman writes:

Many in the legal world still believed in the old virtues even after Bush v. Gore, the 5-to-4 ruling that effectively decided the 2000 presidential election on what appeared to many Americans to be partisan grounds. But now, the court’s hard-right supermajority, installed in recent years through a combination of hypocrisy and sheer partisan muscle, has eviscerated any consensus.

Under the pretense of practicing so-called originalism, which claims to interpret the Constitution in line with how it was understood at the nation’s founding, these justices have moved quickly to upend decades of established precedent — from political spending to gun laws to voting rights to labor unions to abortion rights to affirmative action to the separation of church and state. Whatever rationale or methodology the justices apply in a given case, the result virtually always aligns with the policy priorities of the modern Republican Party.

And that has made it impossible for many professors to teach in the familiar way.

“Teaching constitutional law today is an enterprise in teaching students what law isn’t,” Leah Litman, a professor at the University of Michigan law school, told me.

The Supreme Court’s announcement on February 28 that it would convene a hearing on Donald Trump’s claim of presidential immunity in the week of April 22 (now scheduled for April 25) added more fuel to fire that political partisanship plays a major part in its current decisions. It caused many legal experts to comment on the extended length of time it took the Court to decide to hear oral arguments on the former president’s immunity claim and the fact that it would significantly postpone holding a trial on this claim, possibly until after the November presidential election.

In his article for The Atlantic, Paul Rosenzweig asserts:

None of this is accidental. None of this is required by law. If the Court were of the view that it needed to weigh in but wanted to avoid delay, it could have, and should have, chosen to skip the appeals stage. If it was of the view that a unanimous, well written, narrow appellate opinion would suffice, it could have denied the petition for a hearing after the District of Columbia circuit court had issued its determination.

But it did not. The Court took all of the steps possible to slow the processing of the appeal down as much as the law permits. The only inference one can take from this is that a majority of the Court is making a concerted effort to delay the case.

David Leonhardt of the New York Times comes to a similar conclusion, ending his article on the Supreme Court’s decision as follows:

When urgent action could help a Republican presidential candidate in 2000, the court — which was also dominated by Republican appointees at the time — acted urgently. When delay seems likely to help a Republican presidential candidate in 2024, the court has chosen delay. The combination does not make the court look independent from partisan politics.

Circuit Court Decisions and Rulings

It’s not just the Supreme Court where justices’ political affiliations or partisanship come into play. Harvard Law School Professor Alma Cohen’s recent discussion paper titled “The Pervasive Influence of Political Composition on Circuit Court Decisions” discloses the breadth and depth of that involvement.

(The federal judicial system has three tiers: The bottom tier is federal district courts with individual judges. The middle tier is circuit courts which are federal courts of appeal with panels of judges. The top tier is the Supreme Court with nine justices.)

Ruth Marcus, an associate editor for the Washington Post and a Harvard Law School graduate herself, highlights the importance of Cohen’s discussion paper in her February 20 opinion piece, observing:

Federal judges have argued passionately to me that it disserves the public to reinforce the notion of judges as political actors. I think it’s the opposite: It would be keeping relevant data from readers not to include this information. In recent years, as judicial philosophy has become an increasingly important factor in judicial selection for presidents of both parties, I have made it a practice to note the identity of the president who nominated the judge or judges involved. If judges are behaving in ways that could be predicted by their political affiliations, readers deserve to know. If they are ruling contrary to what might have been expected, that’s significant, too.

Now comes an intriguing study by a Harvard Law School professor that buttresses my point — if anything, it suggests we have underestimated the impact of party affiliation on judicial outcomes. Alma Cohen, whose training is as an economist, examined 630,000 federal appeals court cases from 1985 to 2020 and found that the impact of party affiliation went far beyond hot-button issues such as guns or abortion.

Marcus goes on to note:

Cohen’s hypothesis is that Democratic judges and Republican judges “systematically differ in their tendency to side with the seemingly weaker party.” For instance, in civil litigation between individuals and institutions, such as the corporations or the government, “panels with more Democratic judges are more likely than those with more Republican judges to reach a decision that favors the individual party.”

The same holds true for other types of cases. “In the categories of criminal appeals, immigration appeals, and prisoner litigation, increasing the number of Democrats on a circuit court panel raises the odds of an outcome favoring the weak party,” Cohen wrote.

Based upon our review of Cohen’s paper, among the findings that stand out, are the following:

- Political affiliations can help predict circuit court decisions in case categories that comprise more than 90% of all circuit court cases.

- Political affiliation is also associated with outcomes in a large set of civil cases between parties that seemingly are of equal power. In these cases, the more Democratic judges on the panel, the lower the odds of a panel deferring to the lower court decision.

- A lone Republican judge on a panel with two Democratic judges has a stronger “moderating” effect on the panel majority than does a lone Democrat on a panel with two Republican judges.

In her paper, Cohen makes the point that earlier research has found “party effects on certain sets of cases on ‘ideologically controversial issues’” and that “Democratic and Republican judges might even systematically differ in their personality traits and characteristics.” What Cohen’s research reveals for the first time is the “pervasive” nature and impact of the political composition of the courts on virtually all decisions and rulings. As Cohen clarifies, “Political affiliations are shown by my analysis not to determine outcomes but merely to influence them.”

Within the Republican member judiciary, the nature of that influence appears to vary with judges appointed in the past having been more center-right in their orientation and decisions and Trump appointees being more far right in their decisions and orientation. Ian Millhiser presents an analysis of the impact of this in his April 3 Vox article titled “Why Republican federal judges are fighting among themselves”

The Need for Reform of the Courts

There is no magic judicial wand that can be waved to ensure that rulings are always equitable and nonpartisan in nature. Fortunately, there are numerous recommendations that have been proposed to reduce political influence at both the circuit court and the supreme court levels.

Cohen notes, at the end of the discussion paper, her research can be employed and expanded upon in order to evaluate the current state of the judicial system and reform proposals, including:

- The process of presidential appointments, not only to the Supreme Court but to circuit courts as well, and the impact of these appointments on “subsequent circuit court decisions”

- The process for, and filibuster rules governing, the Senate confirmation of the president’s judicial nominations

- Creating or requiring mixed-party circuit court panels in order to achieve more balanced decisions.

This additional analysis is important. More important, however, is that it not create a state of analysis paralysis where one piece of research leads to another piece of research to another piece of research and no meaningful action.

We already appear to be in that paralysis state with regard to the Supreme Court. As we noted in a 2022 blog, in April 2021 President Joe Biden appointed a Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court to examine issues related to reform of the Supreme Court. The Commission submitted its analysis in a final report, which included arguments for and against changes to the current mode of operations but no definitive recommendations, in December 2021.

Cohen’s research is revelatory. It makes it apparent that political affiliations influence the large majority of courts’ rulings and the evolution of laws and legal doctrine across this nation.

Based upon those findings, we can state unequivocally that the need for court reform is critical and urgent. Because of this, we close with a slightly modified version of the ending of a blog that we posted in 2019 on the need for reform of the Supreme Court:

We believe in a strong, independent and impartial judiciary. We need that for the sake of, and to preserve, American democracy.

This is why we need new rules of engagement for the courts. We need to reform the federal judicial system in a manner that ensures that the courts have the balance of power and provide the balance of perspectives envisioned by the founders.

If they become merely an extension of a political party or an ideology, it puts the future of this democracy at risk. A democracy at risk cannot long survive.