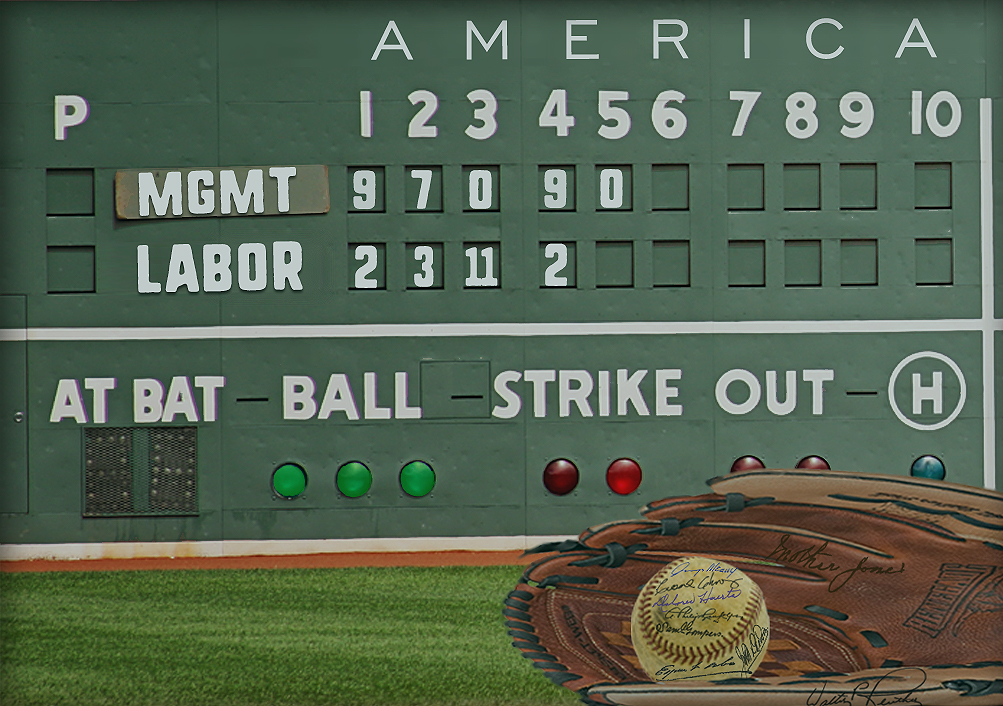

Labor Strikes Out

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, September 4, 2023 (Image credits: Tom de Boor, Adobe, Dreamstime, et al)

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, September 4, 2023 (Image credits: Tom de Boor, Adobe, Dreamstime, et al)

In baseball, if there is a strikeout, the pitcher and his teammates are happy and the batter and his teammates are unhappy. In the labor movement, given the results achieved to date through strikes in 2023, some workers are happy and others are not.

Labor Striking Out Increases

What can’t be disputed is that in 2022, and again in 2023, the strike returned to a position of prominence as a tool used by organized labor and those attempting to organize labor.

As Sarah Chernikoff reported for USA Today on August 6:

With less than half the year left, there have been 177 work stoppages, according to Bloomberg Law’s work stoppage database. That’s compared to the nearly 320 total strikes initiated by unions in 2022.

Last year proved to be monumental for strikers: It was the first time since 2005 strike totals surpassed the 300 mark.

Drawing upon data from the Cornell ILR Labor Action Tracker, on August 6, Annie Nova of CNBC.Com reported a slightly higher number of strikes stating, “More than 200 strikes have occurred across the U.S. so far in 2023 involving more than 320,000 workers, compared with 116 strikes and 27.000 workers over the same period in 2021,…”

No matter whether it is 177 or more than 200, as they did in 2022, employees are striking out, stopping work, and walking off the job. The worker “strikes” that have probably received the most press coverage in 2023 are one that happened and one that didn’t.

The one that happened was the strike on May 2 of 11,500 screenwriters who are members of the Writers Guild of America. On July 14, they were joined on the picket lines by the 170,000 members of the Screen Actors Guild — American Federation of Television and Radio artists. Both groups are looking for higher wages and responses to a number of other factors related to the changing nature of their industry, such as the intrusion of AI and the growth of streaming.

On August 23, The American Association of Motion Picture and Television Producers publicly shared a proposal they put forward to the Writers Guild but it received an unwelcome response from the Guild. There has been no word yet on the Screen Actors negotiations. As of this time, both of these strikes remain unresolved.

The strike that was averted was that of nearly 340,000 UPS workers who are members of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. They would have gone on strike on August 1 if a new contract had not been negotiated. An agreement was reached on July 25, which will give UPS full and part-time drivers a $2.75/hr. raise this year, and $7.50/hr. over the 5 years of the new contract. The contract was ratified on August 22, with over 86% voting in favor of it — ‘the highest vote in the history of the Teamsters at UPS.’

Two other strike targets that evoked considerable press coverage and public interest this year were those at Starbucks and Amazon — both of which are strongly resisting becoming unionized. The major coverage for Starbucks was of a walkout in late June by more than 3,000 employees at over 150 stores across the country to protest management’s allegedly refusing to allow the stores to put up LGBTQ Pride decorations. This walkout is indicative of the substantial strife between labor and management over the past few years. In a May 12 Guardian article, Michael Sainato wrote:

NLRB regional offices have issued 93 complaints covering 328 unfair labor practice charges against Starbucks since late 2021. Four NLRB board members, eight administrative law judges and two federal judges have issued 16 decisions ordering remedies for unfair labor practices by Starbucks, including the reinstatement for 23 fired workers, though some decisions have yet to be enforced, according to the NLRB.

In July, during Amazon’s Prime Day, 60 Amazon workers walked out of a delivery station in Pontiac Michigan for more than three hours, bringing it to a virtual standstill. This was part of a nationwide strike over a three-week period that occurred in eight warehouses in states, including California, Michigan, and New Jersey, seeking safer working conditions and better wages. In spite of these headlines, the union movement at Amazon is still very much in its infancy, and it could be still-born. There is still no Amazon union contract and the Amazon Labor Union, which was started at a warehouse on Staten Island, has yet to bring other locations on board.

Other strikes of note in 2023 include: the walk-off of more than 11,000 Los Angeles city workers for 24 hours on August 8, alleging unfair labor practices; and planned rolling strikes, since July, conducted by hotel workers in the city of Los Angeles and Orange County organized by Unite Here Local 11, seeking to improve worker wages significantly.

There is one potential major strike that could occur in mid-September. If it does take place, it will be the members of the United Auto Workers (UAW). In her article for the Washington Post, Lauren Kaori Gurley notes,

In Michigan, contract negotiations between the United Auto Workers and big Detroit automakers Ford, General Motors and Stellantis began in mid-July and are shaping up to be the most tense in years — with wages and compensation at the heart of talks. The union’s combative new president has all but said that some or all of the UAW’s 150,000 autoworkers will strike if they don’t make progress at the bargaining table.

On August 25, the UAW President Shawn Fain announced that members had authorized the right to strike by a vote of 97%.

Reasons for and Obstacles to Striking Out

As this top-line review shows, for labor striking out can produce mixed results. Given this, what is motivating more workers from a variety of industries to grab a sign and join the picket lines?

There is obviously no single or simple answer to that question, and it’s impossible to read individuals’ mindsets. Nonetheless, major contributing factors for striking out definitely include: inflation, which caused the need for larger raises to cope with the rising costs of everyday goods and services; increasing inequality between the have-a-lots and those who have-a-lot-less; and the pandemic, which caused workers to re-examine what they wanted in and from their jobs.

That said, in January of this year, the Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations released its Cornell ILR Labor Action Tracker Annual Report for 2022 (Report). The Report presents key findings from Cornell’s data on work stoppages last year.

Regarding the primary reasons for work stoppages, The Report states,

The most common demands of work stoppages in 2022 were better pay, improved health and safety, and more staffing. In 2022, an end to anti-union retaliation and reinstate terminated union activist became more common demands among work stoppages.

The Report also states:

Finally, while we documented an uptick in strikes and approximate number of workers on strike in 2022 as compared with 2021, the level of strike activity is lower than earlier historical eras.

Greg Rosalsky reinforces this point in an excellent February 28 NPR Planet Money article titled “You may have heard of the ‘union boom’. The numbers tell a different story.” In his article, Rosalsky notes that “Last year the union membership rate fell by 0.2 percentage points to 10.1% — the lowest on record.” He went on to explain that “… the number of American workers in unions did in fact grow by in 2022 — by approximately 200,000. It’s just that the non-union jobs grew faster.”

The most revelatory part of Rosalsky’s article is where he addresses why unions have had, and will have, such a difficult time in growing substantially during these times. He uses his interview with Suresh Naidu, a professor of economics at Columbia University, who published an article on the future of labor unions in The Journal of Economic Perspectives in the Fall of 2022 to make that case.

Rosalsky summarizes that interview as follows:

American labor law just puts an enormous barrier in the way of workers joining a union,” Naidu says. “So you need to convince 50% plus one of your coworkers to join a union if you want a union.” That alone can entail a difficult and time-intensive campaign process. Meanwhile, he says, our labor laws make it relatively easy for employers to short-circuit organizing efforts. And even when some of their tactics are technically illegal, Naidu says, companies are given wide latitude to thwart unionizing with minimal legal sanctions. Union organizers are forced to strategize and organize outside their workplace and figure out how to convince coworkers to join the fight without getting penalized or fired. “Workers basically have to be like a little Navy SEAL team in order to successfully unionize under the radar of an employer,” Naidus says.

Rosalsky adds to this list of burdens and barriers for unions facts such as: 27 states have right to work laws; globalization, causing companies to move their operations out of the country; and automation replacing workers with machines. The list of obstacles to union growth goes on and on.

The Future for Striking Out

Based upon this context, what is the future of unions? Have the past few years been an aberration or will the union movement continue to evolve, to be renewed, and to grow at an increasing rate? This will be determined by what transpires in the economic, legal, psychological, sociological, political, and policy environment here in the U.S. over the next decade or so.

After reviewing the current state of these environmental conditions, near the end of his Journal article, Professor Naidu comments:

Rapid increases in union density are like wildfires (or pandemic waves), and I have little confidence in predictions about whether worker organizations will grow, or even persist, in the twenty-first century. If they do, I suspect they will be very different from the labor organizations of the twentieth century. These new organizations, possibly incubated inside or alongside existing labor unions, will depend on government in new and multiple ways, deploy collective action at multiple scales for both economic and political goals, and use and bargain over technology in ways that are hard for any middle-aged academic to anticipate. In the current lopsided legal environment, labor market tightness has been an important input into emboldening workers to organize: a sharp recession could quickly restore employer temerity to discharge workers and dampen whatever sparks in labor organizing we have now. But rising unemployment could also trigger even more militant labor activism.

Naidu’s assessment is somewhat pessimistic in tone. In his interview, he sounds a somewhat more optimistic note, stating according to Rosalsky:

However, after years of witnessing a seemingly bottomless decline of unions, Naidu says, he is heartened that there are at least some signs of life. “I would have zero hope if it was not for the Starbucks and Amazon stories,” Naidu says. “But now I have some hope.”

Hope is a starting point and so are strikes. As we noted in the beginning of this piece, striking out can be a good thing or a bad thing, depending on which team you are on and what is done after striking out.

Strikes are tools. They are means and not ends. What matters is how they are leveraged not only to shape negotiations with the organization being struck against but also to influence the broader context for negotiation.

Today much of the legal, political and policy context is tilted against unions and the labor movement. That must be changed for the prospects for unions and American workers to change. As Rosalsky reports, Naidu stressed that in his interview:

To really jumpstart unionization, Naidu believes, America needs big policy changes, including an embrace of sector-level bargaining, an increase in incentives for workers to join unions, and a reduction of incentives for companies to oppose unions. This might include awarding federal contracts only to companies that are pro-union, or imposing steeper penalties on companies that oppose unions.

On this Labor Day, there is nothing nearly of the scope of what Naidu proposes under consideration. There is a Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act in the Congress, which would make some amendments to the National Labor Relations Act favorable to unions ability to organize and engage in collective bargaining, and restrict employers’ and states from interfering with their rights.

It is highly unlikely, however, given the current composition of the U.S. Congress and the run-up to the national elections in 2024, that the PRO Act will ever see the light of day. The results of the 2024 elections at all levels will also have a definite, but not determinative impact, on the future of unions and organized labor.

And their future will have an impact on the future of this country and its citizens. In December 2021, the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) issued a report describing the positive effects of unions. The report opens as follows;

In this report, we document the correlation between higher levels of unionization in states and a range of economic, personal, and democratic well-being measures. In the same way unions give workers a voice at work, with a direct impact on wages and working conditions, the data suggest that unions also give workers a voice in shaping their communities. Where workers have this power, states have more equitable economic structures, social structures, and democracies.

EPI is liberal in orientation but other studies have had similar findings. The bottom line for workers is those who are in unions tend to do better for their bottom lines, and those of others, than if they are not.

In our 2022 Labor Day blog, we stated:

In our opinion, the union movement will be able to take advantage of this moment in time to reverse the decline of unions and to enable them to begin to rebound and recover. We do not anticipate, however, a rebirth of the union movement or the return to membership to what it was a half a century ago.

Our best guesstimate is that there will be incremental progress and growth in terms of the size and influence of organized labor in the decade to come. Because of the substantial strength of employers, we project that the dance for the unions will be two steps forward and one step back.

In 2023, our opinion remains the same. We would like to see more substantial growth and progress and would be pleased to be proven wrong.

This can only be accomplished, however, if labor stays on the playing field and continues to strike out to benefit America and Americans. By doing so, they can gain the momentum and the time to modify the rules of the game and level the playing field so that it is a fair place for workers to engage.

Happy Labor Day!