Decade Lost, Decade Found

![]() By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, February 14, 2020

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, February 14, 2020

The decade 2010–2019 for the United States, to paraphrase T.S. Eliot, was one that “ended not with a bang but with a whimper.”

Some of that whimper was President Donald Trump bemoaning the unjustness of his impeachment by the U.S. House. Some of it was writers looking back retrospectively and commenting on those ten years.

In their assessment, this past decade was not one of joy and American progress but one of sadness and retreat. The cover page of the Sunday Review section of of the New York Times for December 29, 2019 labeled 2010–2019, “A Decade of Distrust.” In a special opinion piece on December 26, 2019, six Washington Post columnists provided their words describing the decade of the 2010s. The labels they applied included “unraveling,” “anxiety”, and “dissonance.”

Reflecting on the Past Decade

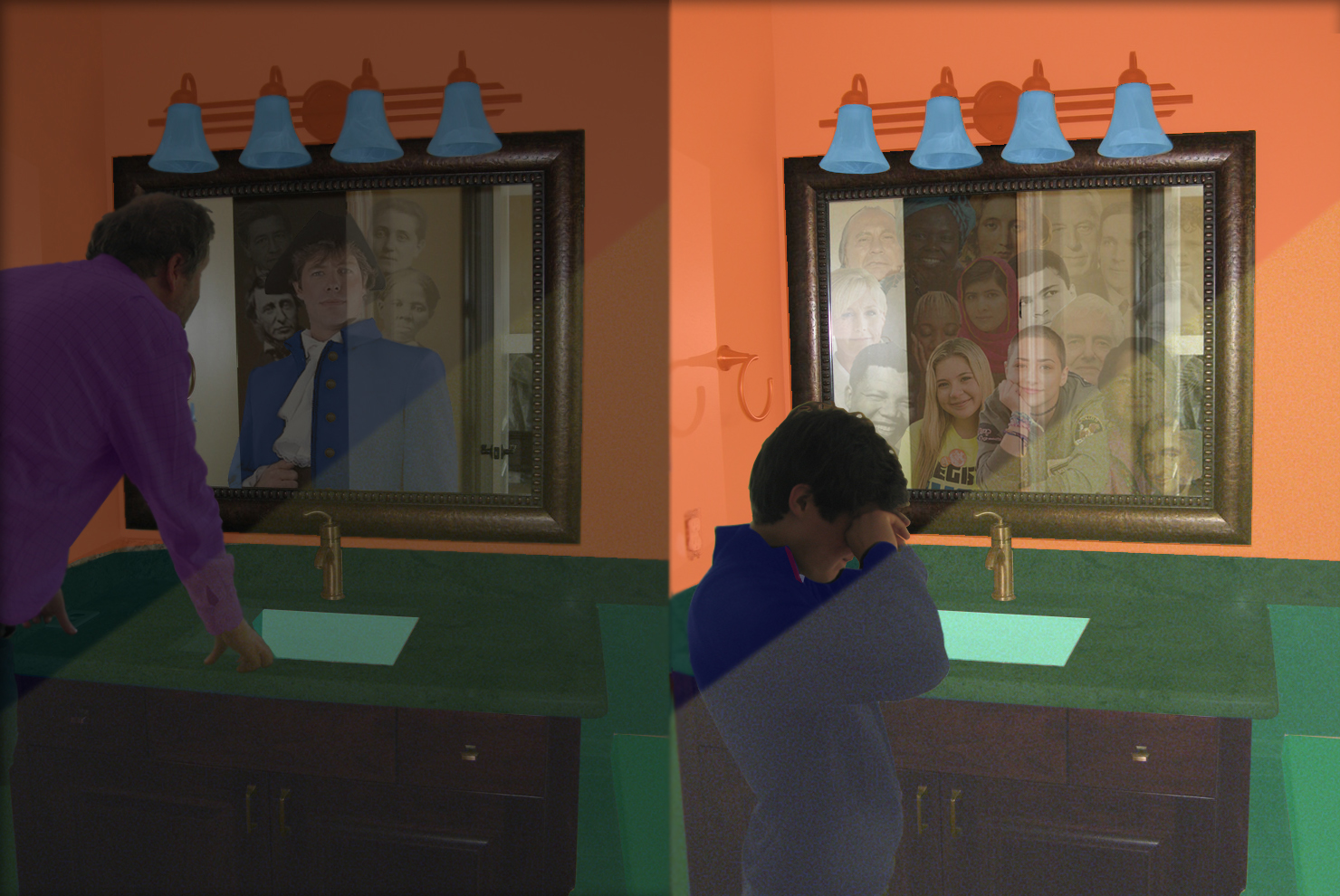

Our assessment is similar to those. We view 2010–2019 as a decade of loss.

The losses came on many fronts. Within the U.S. itself, there was a loss of faith; a loss of hope; and a loss of charity. Around the world, there was a loss of America’s leadership position on major global issues and a loss of respect from other countries for the United States.

The loss of faith ran across the board. It was a loss of faith in our political system, our government, our institutions, and in each other. (See our January 2, 2020 post for specific details and commentary on the nature of this loss.)

The loss of hope was in the American dream and in the American democracy. This loss was driven by increased inequality; a changing middle class; significantly greater influence of the wealthy and big business over government and in society; an almost completely dysfunctional Congress; and a large percentage of jobs that don’t pay a living wage. (We addressed these issues early in the decade in our two books, Renewing the American Dream: A Citizen’s Guide for Restoring Our Competitive Advantage (2010) and Working the Pivot Points: To Make America Work Again (2013). We have also written about them frequently through the decade and in blogs posted over the last two years of the decade.)

The loss of charity came with Donald Trump’s campaigning for and winning the Presidency, and continued into his administration over the past three years. It has a number of dimensions, but has been focused primarily on changes in governmental programs for the poor and the imposition of immigration barriers.

On the poverty front, Trump’s calling for the abolition of the Affordable Care Act without a real replacement for it would have a substantial impact on those of modest means. The reduction of those on food stamps and a new work requirement for those who are able-bodied, which will go into effect in April, would “cut off basic food assistance for hundreds of thousands of the nation’s poorest and most destitute people”.

Trump’s anti-immigrant actions include, but are not limited to: his Muslim travel ban; the internment of illegals in substandard conditions; building of a wall along the Mexican border; and his proposed immigration policy which elevates the importance of those immigrants with money and education securing entrance to the country and eventually achieving citizenship.

The immigration policy that has been proposed by Trump is so radically different than the policy in existence that if it were implemented in full it would necessitate changing the inscription at the base of the Statue of Liberty.

That inscription, penned by poet Emma Lazarus in 1903, concludes as follows:

Give me your tired, your poor. Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free. The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

In 2020, if Trump gets his way, the golden door would become a trap door through which most of ‘those poor, huddled masses’ would fall. If that were to occur, the inscription on the statue should be changed to read,

Send me your educated, your wealthy, your business owners, yearning to make fees. The best you can from your shrinking shores. Send them and only them to me. I lift my lamp for these aristocrats-to-be.

Donald Trump and his administration’s impact on the decade of loss extends far beyond the shores of the U.S.A., to the international arena. Pew Research tracks attitudes and perceptions regarding the U.S. and its Presidents through its Global Attitudes and Trends surveys of a representative cross-section of countries.

Those surveys show that through the past decade until today views of the U.S. have stayed “mostly favorable”. By contrast, President Trump’s ratings are extremely low and much lower than President Barack Obama’s. A Pew survey released in January 2020 disclosed that a median of 64% of respondents had “no confidence” in Trump to do the right thing. Many of his global policies are disliked as well, with a median of 68% in those nations polled disapproving of U.S. tariffs and fees on imported goods and a median of 66% disapproving of the U.S.’s withdrawal from international climate change agreements.

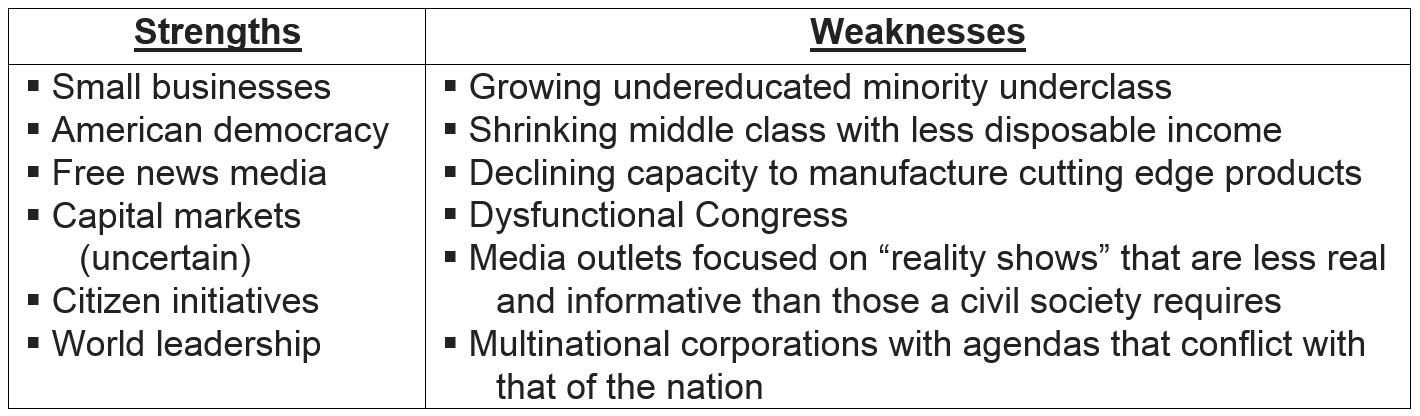

Summing it up, this has definitely been a decade of loss for the United States. We provided the table which follows in Renewing the American Dream. It enumerated some strengths and weaknesses that could be used as a starting point and frame of reference to do the type of planning that “will be required to achieve competitive advantage in the future.”

United States of America Situational Assessment in 2010

As we look at the strengths and weaknesses on that table in 2020, our assessment is that overall the strengths have diminished and the weaknesses have worsened. This does not bode well going into this new decade, nor does the way it has begun.

Contemplating this New Decade

Even though this new decade is only about one and one-half months old, it has already had five disquieting events which suggest that the downward spiral that characterized the end of the 2010s will continue, and could even accelerate in the 2020s. They were:

- President Trump’s State of the Union address

- The Senate’s acquittal of Donald Trump on the impeachment charges

- President Trump’s National Prayer Breakfast performance

- President Trump’s White House event after his acquittal

- The Iowa Democratic caucus catastrophe

President Trump’s words and delivery of his State of the Union address were classically Trumpian. His self-congratulating, overstatements, and numerous falsehoods were bothersome. More bothersome than the address itself was the campaign rally tone and feeling it took on, with Republicans chanting “four more years” at points during Trump’s remarks. Most bothersome by far, however, was the awarding of the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Rush Limbaugh by Trump’s wife Melania during the choreographed proceedings.

The Medal of Freedom is given “to individuals who have made especially meritorious contributions to the security of national interests of America, to world peace or to cultural or other significant public or private endeavors.” Rush Limbaugh has spent his professional career saying and doing things that divide America and Americans and attacking those with whom he disagrees. If these contributions to the creation of a toxic national culture merit the award then, as one pundit observed, perhaps the next recipient should be David Duke.

The Medal of Freedom award, though, pales in comparison to the Senate’s acquittal of President Trump. The facts and evidence were all on the side of the Democrats, but the votes were on the side of the Republicans. And, because of that, in this instance — with the notable exception of Mitt Romney — allegiance to the party and President trumped allegiance to the country and the oath of office.

The Senate’s acquittal moved us further into the alternate reality that President Trump has manufactured, and the post-truth society which he has helped promote. A few senators, such as Lamar Alexander (R-TN), spoke the truth. In Alexander’s statement on his impeachment witness vote, he said:

I worked with other senators to make sure that we have the right to ask for more documents and witnesses, but there is no need for more evidence to prove something that has already been proven and that does not meet the United States Constitution’s high bar for an impeachable offense. …The Constitution does not give the Senate the power to remove the president from office and ban him from this year’s ballot simply for actions that are inappropriate.

That was Senator Lamar Alexander’s truth. But that truth did not set him free to vote for impeachment simply for “actions that are inappropriate” and “proven” to be so. Contrary to Senator Alexander’s explanation, the Constitution says nothing about the Senate being able to avoid its impeachment jury responsibilities, or to let the people decide if an impeachment proceeding is being conducted during a presidential election year.

The person who was set free because of the Senate’s purely partisan decision was Donald J. Trump. Senator Susan Collins (R-Me), in announcing her decision to vote to acquit Trump, said she thought he had learned his “lesson” and would be “much more cautious in the future.”

Senator Collins was engaging in wishful political thinking. She was right and wrong. Trump had learned a lesson, but it was not one of caution. The lesson he learned is that he has been set free to be the erratic, volatile and unpresidential person he has always been, and perhaps become even more dangerous and unpredictable.

Trump demonstrated that propensity and potential at the bipartisan National Prayer Breakfast, and at a partisan White House event convened on the day after his acquittal.

President Trump was derogatory in his comments at the Prayer Breakfast, held before the White House event. At the outset of his speech, Trump stated:

As everybody knows, my family, our great country and your president have been put through a terrible ordeal by some very dishonest and corrupt people. They have done everything possible to destroy us, and by so doing, very badly hurt our nation. They know what they are doing is wrong, but they put themselves far ahead of our great country.

He proceeded to say — apparently in reference to Senator Mitt Romney and Leader Nancy Pelosi:

“I don’t like people who use their faith as justification for doing what they know is wrong,” Trump added. “Nor do I like people who say, ‘I pray for you’ when they know that that’s not so. So many people have been hurt, and we can’t let that go on. And I’ll be discussing that a little bit later at the White House.”

Later that day at the White House event, which went on for more than an hour, Trump kicked off the session by proclaiming “This is really not a news conference, it’s not a speech. It’s not anything…it’s a celebration.”

He rambled through a range of topics, including chiding the Democratic leaders involved with the impeachment proceedings as “horrible,” “vicious and mean:” making rude comments about government officials such as former FBI director James Comey (“that sleazebag”) and former FBI officials Lisa Page and Peter Strzok (“two lowlifes”); and stating, once again, that his call with the Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky was “perfect”.

He rambled through a range of topics, including chiding the Democratic leaders involved with the impeachment proceedings as “horrible,” “vicious and mean:” making rude comments about government officials such as former FBI director James Comey (“that sleazebag”) and former FBI officials Lisa Page and Peter Strzok (“two lowlifes”); and stating, once again, that his call with the Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky was “perfect”.

Trump defenders might excuse his rhetorical excess in these two get-togethers as just Trump being Trump. But there should be no excuse for those who engaged in standing ovations and extended applause for Trump and his legal team at the White House event.

The impeachment proceedings were about serious misconduct. To trivialize that and to turn it into an occasion for chortling and grandstanding means that we are moving into a decade where anything goes — and what goes is decorum and along with it democracy.

There can be no excuse, either, for what happened in Iowa in the Democratic caucus. The caucus catastrophe was and continues to be a complete and utter disaster.

The caucus was held on Monday February 3, and the final results should have been announced by late that evening or early the next morning. Because of technical malfunctioning of an app to be used for reporting purposes and vote count inconsistencies, they were not.

That was bad enough. What made it worse — as in the movie Groundhog Day — the next day repeated itself with no explanation from the Democratic Party about what was going on. And, then repeated itself again.

Groundhog Day was a funny movie, and the Jeep Superbowl ad on February 2 with Bill Murray and some of the other cast from the original movie was funny as well. What happened in Iowa was not funny at all. It was a tragedy.

At the end of the week, the Iowa Democratic Party reported that Senator Bernie Sanders and Pete Buttigieg were in a virtual tie for first in delegates with Sanders winning the popular vote by 6,000 votes. But, by then it really didn’t matter.

The incompetence demonstrated in Iowa led to a crisis in confidence and cast a shadow on the candidates seeking the Democratic nomination for President. The question from the pundits, especially those on the conservative side, became if a party could not be depended upon to do something as simple as accurately count and report votes, how could one expect someone from that party to take on the awesome responsibility of leading the nation and addressing the complex issues that will be confronting it going forward.

Making This A Decade of Recovery

In the early stages of this new decade, the country was not on the road to recovery but was diving deeper into polarizing waters which could lead to a permanent paralysis of the nation and its democracy. What, if anything, can be done to alter this course and to make 2020–2029, a decade of recovery?

For thoughts on that we turn first to Arthur Brooks, David Brooks, Paul Krugman, Ezra Klein, and Yuval Levin. Then, we conclude with thoughts of our own.

Arthur Brooks is a social scientist, university professor and former President of the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. In his keynote address at the National Prayer Breakfast this year, he labeled the biggest crisis facing our nation “…the crisis of contempt — the polarization that is tearing our society apart.”

To respond to this crisis, he asked those in attendance at the breakfast to become missionaries and gave them three homework assignments:

First, ask God to give you the strength to do this hard thing — to go against human nature, to follow Jesus’ teaching and love your enemies…

Second, Make a commitment to another person to reject contempt…

Third, Go out looking for contempt, so you have the opportunity to answer it with love.

David Brooks, a journalist, cultural and political commentator and a “moderate conservative” aligns somewhat with Arthur Brooks but is not quite in the same stream. He begins his January 3 New York Times op ed, titled “An Optimistic History of the Next Decade,” as follows:

Looking back at the 2020’s from our vantage point in 2030, the first great event was the complete destruction of Donald Trump’s Republican Party.

Brooks goes on to observe that “The major events of the decade were cultural not political.” He saw three major trends as part of what might be called a cultural revolution.

- The establishment of “Accountability Clubs” on college campuses driven by students who wanted to create a culture in which facts matter and empathy does as well.

- The rise of a spiritually diverse and religiously eclectic urban church in major cities across the country.

And the most important cultural change:

- “The Civic Renaissance,” which would bring together the smaller civic organizations nationally and create a cooperative AFL-CIO for a civil society.

Brooks is decidedly optimistic in the future perspective he presents; Paul Krugman, his fellow columnist for the New York Times, Nobel Prize-winning economist, and university professor, looking at the current conditions presents a very different and much more constrained perspective.

In an op-ed published near the end of the year, Krugman calls out big money and its undue influence in American society. Krugman asks, “Why do a small number of rich people exert so much influence in what is supposed to be a democracy.” He explains that it’s not just large campaign contributions. It’s billionaire-financed think tanks, lobbying groups, and the revolving door from big business into top government positions that extends that impact.

Krugman concludes: “And when candidates talk about the excessive influence of the wealthy, that subject also deserves serious discussion, not the cheap shots we’ve been seeing lately.”

Where Krugman focuses on the impact of the wealthy on our American society and democracy, Ezra Klein focuses on the impact of our two political parties. Klein, a founder and editor at large of Vox, has just published a new book titled Why We’re Polarized.

In a recent New York Times article adapted from his book, Klein highlights why the current conditions of both major parties have led to — and may lead to even more — polarization and hardening of our political arteries.

Klein states that, “Democrats have become more diverse, urban, young and secular; and the Republican Party has turned itself into a vehicle for whiter, older, more Christian and more rural voters.” He notes that the Democratic diversity is reflected in their trust of 22 out of 30 media sources, compared to the Republicans trust of only 7 sources, with Fox News being two times more trusted by them than any of those sources.

Klein explains that in spite of larger numbers of Americans identifying as or with the Democrats, because of “the distortions of the electoral college, the geography of the United States Senate, and the gerrymandering of House seats,” the Republicans can control power nationally. He suggests a democratization agenda as a way to make things more equal and less polarized.

He observes, however,

…Republicans are trapped in a dangerous place: They represent a shrinking constituency that holds vast political power. That has injected an almost manic urgency into their strategy” (tactical extremism).

In our opinion, this makes it extremely unlikely they will be willing to support democratization in any form.

The consequence of this, Klein warns, could be worse than polarization — “a legitimacy crisis that could threaten the very foundations of our political system. He points out that by 2040 “…70% of Americans will be represented by only 30 senators, while the other 30 percent of America will be represented by 70 senators.”

The political picture of the future that Klein paints is frightening. The prospect that Yuval Levin outlines is more comforting.

Levin is a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and editor of National Affairs. He is the author of the forthcoming book “A Time to Build: From Family and Community to Campus. How Recommitting to Our Institutions can Revise the American Dream.

In a January 19 New York Times article, Levin discusses “… the social crisis and collapse of our confidence in our institutions — public, private, civic and political.” He states,

Each core institution performs an important task — educating children, enforcing the law, serving the poor, providing some service, meeting some need.

He calls out those “…people who should be insiders but who act like outsiders performing on institutions.” In this regard, he criticizes many members of Congress who “… rather than work through the institution, they use it as a stage to elevate themselves…” Levin is also harshly critical of President Trump, asserting “Rather than embodying the presidency and acting from within it, he sees it as the latest, highest stage for his life-long one-man show.”

Levin concludes that it is up to all of us:

“…to ask the great unasked question of our time, ‘Given my role in this institution how should I behave?” … “As a President or a member of Congress, a teacher or a scientist, a lawyer or a doctor, a pastor or a member, a parent or a neighbor, what should I do here?”

Each of these thought leaders provides sound insights and advice. Arthur Brooks’ recommendation to meet the “crisis of contempt” head on and stepping forward individually is spot on. We believe, however, that love in and of itself will be insufficient to fuel a recovery of civility and a revitalization of our democracy and American values.

In our opinion, that will require broad sweeping actions of the cultural type outlined by David Brooks.” It will also require, as Brooks pinpoints, “the destruction of the Donald Trump Republican Party.”

This must be the case because the Donald Trump Republican Party — or as we would call it the party of Trump — is centered on a minority controlling the majority; using the rules of the game to disenfranchise, and demonizing those who are different or on the other side.

As noted by Ezra Klein, this poses a threat to the very foundations of our political system. We believe that is an accurate assessment. We also believe that Paul Krugman’s assessment, that the wealthy and powerful have an undue influence which constrains society and our democracy, is accurate as well.

If all of this is true, what do we as concerned citizens do if we want to make this decade — the period from 2020 through 2029 — a decade of recovery? This brings us back to Yuval Levin and his prescription, which is to get involved as individuals and collaborate with others in order to strengthen our institutions and revive the American dream.

21st Century Citizenship and the Road to Recovery

Levin’s prescription sounds very similar to one that we advanced in Renewing the American Dream at the beginning of the decade just past. In that volume, we called for and set out the following framework for 21st century citizenship:

The over-arching role for the 21st century citizen is to be a “capital creator”. The fundamental responsibility for each of us to fulfill that role is to build our own individual capital by becoming a peak performer — to use Marine terminology, ‘to be the best that you can be.’

We can then engage and contribute fully to the seven other areas of capital formation — social, economic, intellectual, organization, community, spiritual, and institutional. To maximize our contributions in those areas, we will need to be:

- Interested — concerned about the common good and the American community as opposed to purely pecuniary or personal concerns

- Issues-oriented — focused on areas of civic and social concern as opposed to rigid ideologies

- Informed — dedicated to gathering and analyzing objective data as the basis for civic and social engagement

- Independent — committed to exercising personal judgment as opposed to taking totally partisan positions, and

- Involved — engaged actively in addressing those issues that are of paramount concern to our community and nation.

The circumstances, interests and capacity of each 21st century citizen will vary. Therefore, each of us will have to determine where, when, and how to be involved.

Being on the sidelines or being a spectator, however, is not an option. We must recognize that as Americans, we have the broadest set of rights in the world and that along with those rights come responsibilities. We must commit ourselves to our own courses of action based upon that understanding and recognition.

We elaborated upon the 21st century citizenship concept as follows:

You might be reading this and saying to yourself that a single person or a small group can’t make a difference. In fact, from the establishment of the nation until today, individual citizens have been leaders in bringing about the reforms and changes required in our society and in governmental policies and programs.

Senator Bob Graham describes ten of these citizens, such as Candy LIghtner the founder of Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD), in his new book, America, the Owner’s Manual. He also sets out a systematic methodology that can be employed to “make government work for you.” Graham’s book, along with various material available from Public Agenda, a non-profit organization that has been working around the country since 1975 to promote greater community engagement and a more citizen-centered approach to politics, are excellent ‘how to’ references that we as citizens can employ to initiate and work on changes in the governmental arena.

America is the world’s grandest experiment. America is and always will be a work in progress. When someone says something can’t be done, we do it. When someone says our best days are behind us, we prove them wrong. When someone says we can’t get along, we unite. When someone asks where do we start, the 21st century citizen responds, “let the renewal begin with me.”

We reiterate that call again at the start of this new decade. The need now is much greater than it was then because ten years have been lost and the circumstances are more dire now. That is why in 2018 we established the Frank Islam Institute for 21st Century Citizenship to be a go to resource for those interested and committed to making a difference through civic learning and engagement.

2020–2029 must be the decade of recovery because time is running out for the United States as we have known it and want it to be known. Recognizing this, we must step forward as 21st century citizens.

If we do not, this democracy will end not with a bang or a whimper, but in silence. And that silence will be deafening.