21st Century Workforce Development

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, June 11, 2024 (Image credits: Tom de Boor, Adobe, Dreamstime)

By Frank F Islam & Ed Crego, June 11, 2024 (Image credits: Tom de Boor, Adobe, Dreamstime)

The American economy in 2023 has proven to be tremendously resilient. The recession which had been forecast by many experts has not occurred. The rapidly rising inflation has been slowed and declined considerably. And the national unemployment rate stands close to a near record low.

That was the opening paragraph for a blog on America’s human infrastructure needs that we posted on September 13, 2023.

In 2024, the American economy remains robust. The labor market is strong. New jobs continue to be created.

That is definitely good news. Unfortunately, employers are struggling to fill many of those jobs. Because of these unfilled jobs, investments are required to revitalize America’s human infrastructure and address its workforce development needs.

The Scope and Nature of Job Openings

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce (U.S. Chamber) tracks the status of America’s job openings and labor shortage through its America Works Data Center.

On May 2, the U.S. Chamber released a report written by Stephanie Ferguson, stating:

We hear every day from our member companies — of every size and industry, across nearly every state — that they’re facing unprecedented challenges trying to find enough workers to fill open jobs.

Right now, the latest data shows that we have 8.8 million job openings in the U.S., but only 6.4 million unemployed workers. We have a lot of jobs but not enough workers to fill them. If every unemployed person in the country found a job, we would still have nearly 2.4 million open jobs.

The Chamber put that shortfall into context in an earlier report, writing:

The U.S. continues to battle a years-long labor shortage. The total number of working Americans has surpassed pre-pandemic levels, albeit at a slower growth rate than much of recent history.

Specifically, there are 167.8 million people in the labor force today. That number is expected to grow to 169.6 million over the next 7 years

Despite this growing number, the labor force participation rate has trended downward for more than 20 years with no plateau. In 2000, the labor force participation rate for men reached over 75%, while women’s rate hovered around 61%. In 2020, men’s and women’s annual average LFPRs dropped to 67.2% and 56% respectively. The participation rate is climbing back upward but lags by 6.8% for men and 3% for women from the 2000 rates.

The primary factors contributing to the labor force shortage cited by the Chamber were:

- Early retirements and an aging workforce

- Net international migration to the US at its lowest level in decades

- Lack of access to childcare

- New business starts

- An increase in individual savings

These and other factors will require a comprehensive and coordinated set of solutions. The U.S. Chamber notes that it is “driving solution through the America Works Initiative.”

One of the critical solution areas is education and skills development. This will be necessary across-the-board, because the labor shortage exists from lower skill to higher skill jobs in virtually every industry and in states and places across this nation.

The Need for Development of the Infrastructure Workforce

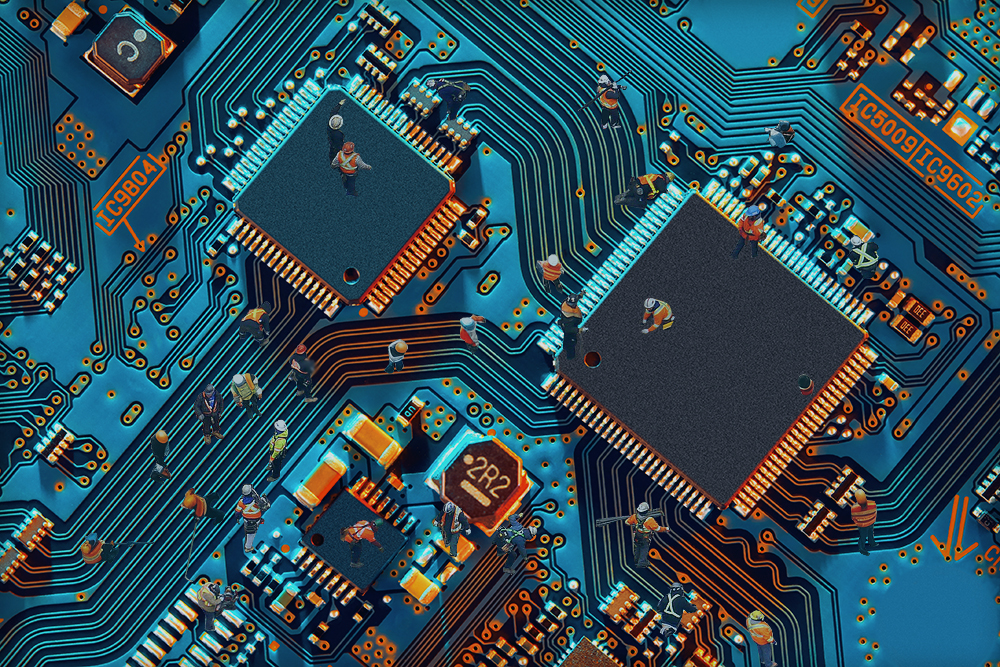

Due to the major federal investments over the past three years in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the Inflation Reduction Act, and CHIPS, the need for infrastructure workforce development will be especially important.

Joseph W. Kane and Robert Espinoza make the case for training and skill development of future infrastructure workers in their March 20 commentary for the Brookings Institution. In their commentary, they note that:

According to the National Skills Coalition and Blue Green Alliance, these laws will generate nearly 3 million jobs on average per year and 19 million jobs in total — an awe-inspiring forecast. This research also shows that 69% of these jobs will be available to workers without a bachelor’s degree, compared to 59% across all jobs in the U.S.

Kane and Espinoza proceed to comment that:

But maximizing the reach of this funding will necessitate significant investment in training and skills development for workers across a variety of occupations. That’s especially the case for investment in short-term training programs and on-the-job training programs, which have often lacked such support.

Such training programs will be vital for construction and manufacturing occupations, which represent two out of every three jobs these federal investments will directly create. Thousands of construction laborers, powerline installers, plumbers, electricians, and others will need quality non-degree credentials, related skills training, apprenticeships, and other workforce programs. If they are to rebuild our physical landscape, we must rebuild the pathways to those good careers across the infrastructure sector.

They add that targeted outreach to women and people of color who are underrepresented in the infrastructure will be key too.

Kane and Espinoza stress that “Durable funding for inclusive education and training programs is a must including pre-apprenticeships, registered apprenticeships, and post-secondary education programs that support skills development.”

In her research article, Martha Ross of the Brookings Institution sets out various actions education and training leaders can take to pursue funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act, which contain no specific provisions for workforce development.

The National Skills Coalition has issued Building The Future Workforce: A State Playbook to Shape a New Age in Federal Infrastructure Investments. The policy playbook “presents a comprehensive set of strategies aimed at empowering state policymakers, governors, and state agency leaders to cultivate a strong, diverse, and multigenerational workforce capable of driving the development and maintenance of our nation’s new infrastructure.”

The Need for a Quality Workforce Development Approach

Proper funding and policies are important ingredients for workforce development. But quality workforce development demands putting a rigorous and integrated approach in place to manage the education, training, and placement process.

A May 1 Washington Post article by Heather Long, Kai Ryssdal, and Maria Hollenhorst, based upon their visit to Phoenix, Arizona, to examine actions being taken to prepare students for jobs in the chips industry generated via the $350 billion in funding in the CHIPS Act passed in 2022, emphasizes that for a variety of reasons this is not a simple task.

In their insightful article, the authors report:

To prepare enough Americans to run the industry, the United States has to rapidly expand community college training, high school vocational programs, and apprenticeships. This might sound easy. It’s not. Even in Arizona, a lot of people have never heard of the semiconductor industry. Recruiting students to enroll is a challenge. Finding experienced technicians to teach courses is hard. And then there’s the most surprising roadblock of all: This is an industry with cycles of boom and bust. Right now business is slow, and some companies are doing layoffs.

The surprising reason among this group of reasons was the lack of currently available jobs in the semiconductor industry. Long, Ryssdal, and Hollenhorst state “At some point, the industry will no doubt have an explosion of jobs.”

That explosion is not here yet, however. Due to this, Maricopa Community Colleges “has sharply scaled back its offerings.”

Such a disconnect between career and technical education programs and job placement is not unusual. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) released a study in 2022 of career and technical education (CTE) programs for high school and college students in four states, based upon a performance audit conducted between 2020 and 2022. One of the central findings from that GAO CTE study was that there was limited long term data available, “such as whether students who progress through a career pathway eventually work in that field.”

During their trip to Arizona, Long, Ryssdal, and Hollenhorst discovered that this disconnect can be eliminated by implementing “earn while you learn” apprenticeship programs. Based upon visiting the Arizona Pipe Fitters Apprenticeship Training Center and the SMART Local 359 Training Center for sheet metal workers, they concluded that “the ideal training model in the semiconductor industry is apprenticeships.”

Later in their piece they observed, “There’s a long way to go, especially on integrating hands-on work with a recognized community college or credential-granting institution. A national push would be ideal.” They proceeded to recommend that “the newly formed National Semiconductor Technology Center should partner with the National Science Foundation, the nonprofit SEMI Foundation, and major companies to come up with standardized credentials for technician roles.”

The Need for Competency-Based Programs

We agree with that recommendation. Replicating something similar would be beneficial for employers and employees in numerous American industries because it would develop the essential core competencies that would be transferable from one organization to another.

We have been advocating for the development and enhancement of competency-based programs since the publication of our book, Renewing the American Dream: A Citizen’s for Restoring Our Competitive Advantage, in 2010. In Renewing, we wrote:

In the classroom students gain knowledge. It’s what we learn in the work setting that develops the skills, abilities, and habits that form a competency.

Think about it. On-the-job training and mentoring are critical for developing the skill sets to make individuals peak performers and to make organizations successful.

It’s why accounting firms take the graduates right out of school and spend a couple of years or so to make them real “accountants.” It’s why medical school graduates do internships. It’s why folks with IT degrees who are sophisticated at programming are trained in project management skills by the firms that hire them. Hotel and restaurant workers are put through some type of orientation and work with a lead employee to learn the ropes. Manufacturing employees do apprenticeships. Those who want to become teachers student teach.

Historically, despite the preponderance of training directed at developing competencies, much of it has not been done well.

We went on to explain that the trade associations in the metalworking industry corrected that problem though the National Institute for Metalworking Skills (NIMS). NIMS developed standards and competency-based assessments for occupations in the metalworking industry. NIMS developed a competency-based apprenticeship program for the metalworking industry. After that, NIMS created a competency-based structured O-J-T program to enable metalworking companies to do a high-quality job in training their own trainers.

Back then, we said that the NIMS model was an excellent one for industries and organizations to look at as they develop their own competency-based programs. Today, the number of excellent models and resources have grown.

There is a wealth of material available through organizations and groups such as The Manufacturing Institute, the National Skills Coalition, Advance CTE, the National Association of Workforce Development Professionals, The American Society for Training and Development, the International Society for Performance Improvement, and many others that can be drawn upon for the development of competency-based programs.

The Needs of 21st Century Workers

In conclusion, we leave you with this thought drawn from our book (https://workingthepivotpoints.com/), Working the Pivot Points: To Make America Work Again (Pivot Points), published in 2013.

We define pivot point as an area that must be leveraged and addressed effectively in order to effectuate change and achieve positive outcomes.

Pivot points define the character and shape the destiny of a nation and its people. They establish the rules of the game and influence the attitude of the public. They create an upward or downward trajectory and accelerate or decelerate forward movement and progress.

In Pivot Points, we discuss the fact that due to accelerating innovation and advanced technology “middle skill jobs” were shrinking and “high skill jobs and low skill jobs” were increasing.

This created a three-part need (1) to ensure the proper training for the new jobs that are being created, (2) to provide retraining for those today in middle skill jobs, and (3) to address the issue of those individuals who are working in low-pay and low wage jobs.

In 2024, that three-part need has been magnified by: AI; the federal government’s infrastructure-related investments; and an economy that continues to generate job of all types and at all levels.

To address those needs appropriately in order to develop a 21st century workforce, the 21st century worker at all skill levels, in the private, public, and non-profit sectors alike, must be properly prepared and rewarded by 21st century organizations.

If this is done, they will prosper and so will this nation. If this is not, they and we will all pay the price.